Migration data in Western Africa

Western Africa1 has long been characterized by high levels of mobility, a trend that far predates the current configuration of borders established during the colonial era. An estimated 7.6 million international migrants resided in the sub-region as of mid-year 2020 (UN DESA, 2020), and this number is likely underestimated, as high levels of temporary and seasonal migration common to Western Africa are not fully captured by existing data. In recent times, this movement has been facilitated by regional policies of the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS), notably the free movement of persons regime that has been put in place since the late 1970s. While more than five out of eight migrants from Western Africa continue to stay within the region, increasing numbers are also moving to different destinations in Africa and beyond in search of job opportunities and better economic prospects.

Recent trends

COVID-19

The COVID-19 pandemic has impacted mobility and migration throughout Western Africa. All countries in the sub-region closed land and air borders and some limited internal movement and barred citizens from reentry. At the height of restrictions in April 2020, IOM estimated that 21,000 migrants were stranded in West and Central Africa (IOM, 2020a).

IOM recorded a sharp decrease in migration flows through key transit points in March and April 2020 after restrictions were put in place. However, flows increased over the following months, and sustained cross-border movement was observed in many countries despite official border closings (IOM, 2020b; IOM, 2020c). As of October 2020, almost all countries had reopened for international flights, but many land borders remained closed.

COVID-19 has also impacted census preparations in the region. Although censuses were scheduled in eight countries in 2020, several are considering postponement until 2021.

Host countries

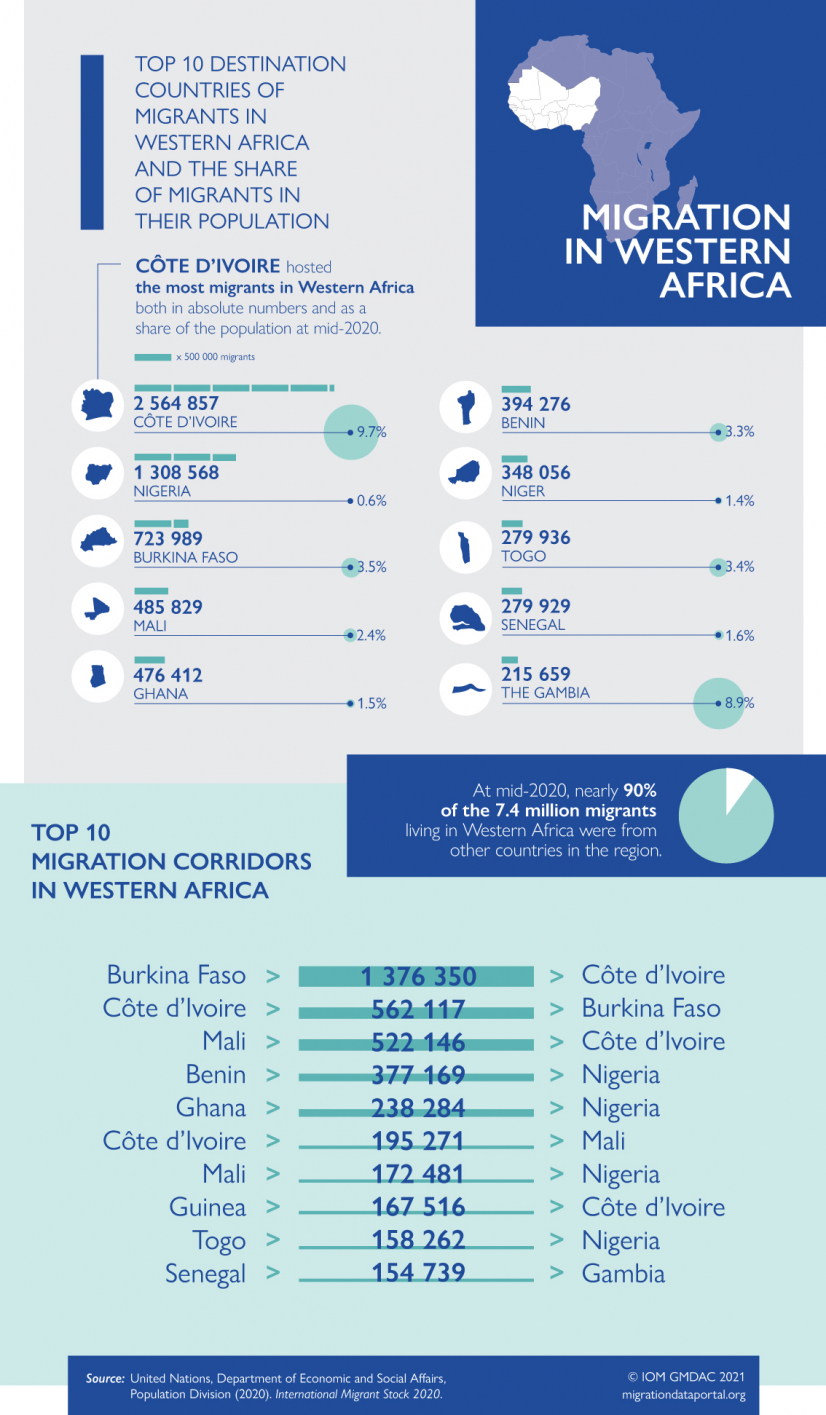

Western Africa hosted 7.64 million international migrants at mid-year 2020. Almost 34 per cent (2.6 million) lived in Côte d’Ivoire and 17 per cent (1.3 million) in Nigeria (UN DESA, 2020).

Destination countries

Most migrants from Western African countries stay in the region, with 2 out of 3 living in another Western African country in 2020. However, migration destinations have diversified in recent years. The share of Western African migrants residing in North America rose from 3 per cent of all emigrants from Western Africa in 1990 to 10 per cent at mid-year 2020, and the share in Europe rose from 12 per cent to almost 19 per cent during the same period (UN DESA, 2020).

Reasons for migration

As in other parts of the world, most migrants from Western Africa are seeking employment and better economic opportunities. Afrobarometer found that economic considerations (including “finding work”, “economic hardship”, “poverty” and “better business prospects”) were cited as the most important reason for considering emigration by between 70 and 90 per cent of respondents in all 14 Western African countries surveyed.2 Pursuing an education, joining family members abroad and adventure were other commonly cited reasons, but did not account for more than 25 per cent of responses in any country (Afrobarometer, 2019).

Labour migration

A large percentage of migrant labourers work in the informal sector, similar to the general population in this region, where informal employment is a predominant feature (Awumbila et al, 2014; Mbaye and Gueye, 2018). Labour migration takes many forms, including temporary, seasonal and permanent migration (ICMPD and IOM, 2015), and implicates many sectors of employment, such as mining in Guinea, Burkina Faso, Mali and Senegal. 3.7 million migrant workers were estimated to live in ECOWAS countries in 2017, including 1.6 million women, and young migrants (15-35 years old) made up 46 per cent of all migrant workers (African Union, 2020).

Remittances

Western African countries received 27 billion USD in remittances in 2020. Nigeria, the largest recipient in Sub-Saharan Africa in absolute terms, received nearly 64 per cent of this total (17.2 billion), while the Gambia (15.6 per cent) and Cabo Verde (13.9 per cent) received the most remittances as a share of GDP. Though estimates for 2020 show that remittances to the sub-region dropped by 19.3 per cent due to COVID-19, remittances to five of the 15 countries for which data are available increased. Remittances received in Nigeria fell by 27.7 percent in 2020 whereas remittances received in Gambia increased by 5 per cent (World Bank, 2021).

Forced displacement

Internal and cross-border displacement in the Lake Chad Basin and Central Sahel regions has risen sharply in recent years:

Central Sahel: The Central Sahel is home to one of the world’s fastest growing crises, with the lives and livelihoods of increasing numbers of civilians disrupted by insecurity and violence. In Burkina Faso, the number of people internally displaced by conflict grew from 47,000 in 2018 to more than 1.1 million as of March 2021 (IOM, 2021). The crisis in the Central Sahel has also resulted in 331,206 IDPs in Mali and 138,229 IDPs in Niger due to escalating violence and climatic shocks (IOM, 2021).

Lake Chad Basin: The decade-long Boko Haram insurgency in Nigeria continues to cause widespread insecurity and displacement throughout the Lake Chad Basin. As of April 2021, more than 2.9 million people were internally displaced across the impacted areas of Cameroon, Chad, Niger and Nigeria, 72 percent (more than 2.1 million) in Nigeria. More than 256,000 refugees were also displaced by the crisis in the Lake Chad Basin, primarily in Cameroon and Niger (IOM, 2021).

Arrivals in Europe

The number of migrants crossing to Europe via the Central Mediterranean Route (CMR) and Western Mediterranean Route (WMR) declined between 2017 and 2019, and remaining arrivals from Western Africa shifted heavily from Italy to Spain starting in 2018 (Fedorova and Shupert, 2020). Arrivals in Europe continued to decrease on the WMR during the first half of 2020, but increased in Italy and Malta (Schöfberger and Rango, 2020). The number of migrants crossing from Western Africa to Spain’s Canary Islands increased sharply in 2020, with 16,760 newly arrived between January and November 2020, a more than 1,000 per cent increase compared to the same period in 2019 (IOM, 2020f).

Assisted voluntary return and reintegration (AVRR)

Niger was the top host country for assisted voluntary return and reintegration in 2019, with more than 16,000 beneficiaries assisted by IOM. Five of the top ten countries of origin for AVRR beneficiaries were also in Western Africa and beneficiaries from the West and Central Africa region made up 35 per cent of the total IOM AVRR caseload. 88 per cent of these migrants were men, and 8 per cent were children (IOM, 2020g).

Transhumance

Transhumance movements are an important component of both internal and cross-border mobility in many countries in Western Africa but cannot be measured through most existing migration data efforts. In some Sahelian countries, livestock production accounts for 40 per cent of the agricultural GDP, but increasing agricultural development, conflict and climate change have impacted traditional movement patterns (IOM, ICMPD and ECOWAS, 2019). The IOM Transhumance Tracking Tool has recently been implemented in Burkina Faso to quantify and anticipate transhumance movements (Jusselme, 2020).

Past (and present) trends in migration

Early history through the colonial period

West Africa has long been known for high levels of intra-regional migration. People traditionally moved for reasons including trade, agriculture, environmental degradation/climate and conflict (Adepoju, 2005; Bakewell and de Haas, 2007).

The beginnings of colonialism disrupted customary migration patterns. European traders enslaved and forcibly transported between 12 and 15 million people from West and Central Africa to the Americas between the 16th and 19th centuries. The introduction of borders and regulations on movement by colonial governments in the 19th century decreased intra-regional mobility (de Haas et al, 2019), and colonial economic policies further altered migration patterns. Both contract and forced labour recruitment and increased transportation infrastructure resulted in high levels of migration from the Sahelian region, particularly Mali and then Upper Volta to plantations and mines in then Gold Coast (Ghana) and Ivory Coast (Côte d’Ivoire) (Adepoju, 2005).

Immigration from outside Western Africa remained low during the colonial period, barring exceptions such as the migration of Black American settlers to Liberia in the mid-19th century and migration from Lebanon starting in the late 19th century. Relatively few Europeans permanently settled in the region compared to Northern or Southern Africa.

Post-independence

Most Western African countries achieved independence by the early 1960s. However, migration patterns established under colonialism largely continued. Both long-term and seasonal labour migrants regularly moved from landlocked countries in the Sahel to the coastal zones in Ghana, Côte d’Ivoire and Senegal that were home to significant cash crop production (Yaro, 2008). Migration across porous national borders, which were often drawn without accounting for the distribution of ethnic and language groups, remained common (Adepoju, 1997). After the 1973 oil shock, Nigeria also became host to increasing numbers of migrants (Yaro, 2008).

The Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS), founded in 1975, further encouraged intra-regional migration through an easing of restrictions on movement between countries. At the same time, economic crises resulted in both the mass expulsion of migrants, most notably in Ghana (1969) and Nigeria (1983 and 1985), and high levels of return migration from former migrants in Côte d’Ivoire (Bakewell and de Haas, 2007; Yaro, 2008).

In addition to economic migration, conflicts in Liberia (1989—1996), Sierra Leone (1991—2001) and Côte d’Ivoire (2002—2004) from the 1990s to early 20th century resulted in significant internal displacement and large refugee populations throughout the sub-region.

Present day

Migration levels remain high in Western Africa today. The total number of emigrants more than doubled in the past 30 years, although their share of the population remained largely stable between 2.8 per cent at mid-year 1990 and 2.6 per cent at mid-year 2020. This percentage varies greatly among countries, ranging from 0.8 per cent in Nigeria and 1.7 per cent in Niger to 7.758 per cent in Burkina Faso and 33.7 per cent in Cabo Verde (UN DESA, 2019UN DESA, 2020).

Most Western African emigrants move to a neighbouring country, but the share of extra-regional migration has increased. As of mid-year 2020, 64 per cent of migrants from Western Africa lived in another country in the region, down from 80 per cent as of mid- year1990. The highest levels of intra-regional migration are from lower-income or landlocked countries (with the notable exception of Côte d’Ivoire). Over 97 per cent of migrants from Burkina Faso live in another country in Western Africa, as do over 90 per cent of migrants from Niger and over 75 per cent of migrants from Benin, Côte d’Ivoire, Mali, and Togo (UN DESA, 2020).

Migrants from more prosperous coastal areas increasingly emigrate outside the region, including Nigeria, Ghana and Senegal. The percentage of Western African migrants in Europe grew from 12 per cent at mid 1990 to 19 per cent at mid-2020, and the share in North America increased from 3 per cent to 10 per cent over the same period, with destinations driven in part by residual colonial ties and common languages (UN DESA, 2020).

Migration to Western Africa has increased in absolute numbers but has declined as a share of the population, from a high of 2.5 per cent in 1990 to 1.9 per cent in 2020. However, this declining trend is largely explained by a fall in refugee numbers since the 1990s. Côte d’Ivoire continues to host the most migrants, both in absolute numbers and as a percentage of its population. Nigeria hosts the second highest number of migrants, at 1.3 million, while the Gambia is home to the second highest share of migrants as a percentage of its population, at 8.98 per cent (UN DESA, 2020).

After conflicts in Liberia, Sierra Leone and Côte d’Ivoire ended, forced displacement in Western Africa fell dramatically. By 2009, refugee numbers in the region had dropped to less than 12 per cent of their peak from the 1990s (UNHCR, 2020). Nevertheless, new displacement tied to escalating violence in the Lake Chad Basin and Central Sahel regions has risen sharply in recent years (see Recent Trends).

Back to topData sources

Sources of regional data on migration in Western Africa are very limited. Although ECOWAS is working to harmonize data collection among countries in the region, it currently publishes very little data. However, many international organizations publish data that include Western Africa, and country-level census and survey data are increasingly available online.

Regional and international data sources:

- ECOWAS publishes statistics on the number of resident foreigners at the country and regional level. These data were last updated in 2016.

- UN Department of Economic and Social Affairs (UN DESA) produces regular estimates of international migrant stock disaggregated by age, sex, origin and destination.

- IOM collects a variety of data on migrant and IDP populations through the Displacement Tracking Matrix (DTM), including information on stocks, flows, profiles, vulnerabilities and living conditions. Some datasets are open, while other data are provided through dashboards and reports. DTM is currently operating in Burkina Faso, Guinea, Mali, Mauritania, Niger, Nigeria and Senegal. IOM also publishes regular reports with data on migrants who were aided by its assisted voluntary return and reintegration (AVRR) programs, including information on host and origin countries, sex, age and vulnerabilities.

- The International Labour Organization’s data portal, ILOSTAT, includes multiple country-level indicators on labour migration and occupational injuries disaggregated by migration status.

- UNHCR manages the Refugee Population Statistics Database, which includes data on refugees, asylum seekers, IDPs and other populations of interest, reported by country of origin and country of asylum. Dashboards for specific countries in Western Africa can be found at the UNHCR Operations Portal.

- International Displacement Monitoring Centre (IDMC) publishes data on internal displacement stocks and new displacement from conflict and disaster through its Global Internal Displacement Database.

- The Counter Trafficking Data Collaborative (CTDC) publishes anonymized data on identified cases of human trafficking contributed by counter trafficking organizations.

- The World Bank produces data on remittance inflows and outflows.

- Afrobarometer published data on emigration plans and reasons for emigration in 14 Western African countries from its public attitude surveys (2016-2018).

- The African Union has released two reports on labour migration statistics in Africa, with estimates on the number of migrant workers in ECOWAS.

Censuses and household survey data:

- Population and Housing Censuses: 15 countries in Western Africa conducted censuses during the 2010 census round. The United Nations Statistics Division compiles census questionnaires for most countries, and reports and some data, including information on migration, are available through individual countries’ national statistics offices.

- Labour Force Surveys: At least 10 Western African countries have carried out labour force surveys in recent years. The ILO provides a list of questionnaires and reports by country.

- Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS): All countries in Western Africa except Guinea-Bissau have conducted DHS surveys. Datasets and reports are available online, although limited information on migration is included.

- Living Standards Measurement Study (LSMS): The World Bank’s LSMS surveys have been carried out in six countries in Western Africa. The data are available online but include limited information on migration.

Other sources of data and analysis:

- The Mixed Migration Centre’s (MMC) Mixed Migration Monitoring Mechanism initiative (4Mi) collects data through individual interviews, covering topics including routes, motivation and vulnerabilities. In Western Africa, 4Mi collects data in Burkina Faso, Mali and Niger. Data are not published, but MMC produces reports and other analysis.

- UN OCHA manages the Humanitarian Data Exchange (HDX), an open data platform for sharing humanitarian data. Many intergovernmental, governmental and civil society organizations working in Western Africa upload datasets to this platform.

- REACH publishes granular data and analysis in crisis areas through its Resource Centre. They currently work in Mali, Burkina Faso, Niger and Nigeria.

- ACAPS produces data-based reports and analysis on humanitarian issues in Burkina Faso, Mali, Niger, Nigeria and Senegal.

Strengths and limitations of data sources

Timely, reliable data on migration are lacking in most West African countries, and existing data are difficult to compare and aggregate as definitions of migration, reference periods and classification schemes are not harmonized across countries (IOM and FMM West Africa, 2018; African Union, 2020).

Most demographic data in the sub-region come from censuses, which provide comprehensive coverage of the entire population but lack timeliness (MMC, 2017). These data are often inconsistent as some countries do not disaggregate migration data by age or use common age categories (Awumbila et al, 2014). Migration may be measured by country of birth or citizenship (MMC, 2017), and coded response categories are inconsistent, meaning that the specific country of origin for many migrants cannot be identified (IOM, 2008). Representative household surveys can provide far more detail than censuses, but few surveys in Western Africa include questions on migration, sampling frames are not always appropriate for accurately measuring migration and migration-specific surveys are rare (IOM, 2008).

Data on migrant stocks produced by national statistics offices and UN DESA are the most reliable information on migration available in Western Africa. Comparable national statistics on migration flows and emigration are limited as few countries include relevant questions in censuses and household surveys (IOM, 2008; Awumbila et al, 2014), and administrative data are not well developed for measuring migration in a statistically robust way (IOM, 2018). Some migration topics of particular interest in Western Africa, such as temporary, circular and irregular migration, are particularly difficult to capture via commonly used data collection methods (Awumbila et al, 2014).

International organizations like UN DESA, the ILO and UNHCR use a variety of methodologies and data sources, including census and survey data, registration and estimation methods, to overcome differences in the availability and quality of country-level data and produce comparable statistics. As such, the reliability of data produced is heavily dependent on these underlying sources and methods. Data from UN DESA are regularly updated for all countries. However, these data are frequently inconsistent with national sources. For example, Côte d’Ivoire’s most recent census in 2014 counted more than twice as many immigrants living in the country as UN DESA numbers from a similar period (Fargues, 2020a, UN DESA, 2019). Similarly, national sources of data in Mauritania and Niger record far fewer emigrants than UN DESA (Fargues, 2020a).

Non-representative data sources, like DTM and 4Mi, provide much more timely data than censuses or household surveys. They also capture information on topics of interest to policymakers that is not commonly available from other sources, such as migration flows, irregular migration and the experiences and needs of people on the move. However, these data are only available for select geographic areas and are not representative, which makes analysis more challenging (Fargues, 2020b).

Back to topRegional processes

The Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) is the primary actor regulating migration in West Africa.3 ECOWAS has focused on intra-regional mobility since its establishment in 1975. Its founding treaty, and the revised 1993 Treaty, specifically call for the removal of obstacles to the free movement of goods, capital and people in the sub-region.

In order to operationalize these commitments, ECOWAS Member States approved the 1979 Protocol Relating to the Free Movement of Persons, the Right of Residence and Establishment, formally establishing a binding, legal framework for migration within West Africa. The rights outlined in this and supplementary Protocols were to be progressively implemented in three phases within 15 years of ratification, but implementation has lagged.

- Phase 1, the right of entry, entitles all ECOWAS citizens with valid travel documentation to enter ECOWAS Member States without a visa for up to 90 days. This right has largely been achieved, despite lingering issues with identity documents and harassment at border crossings (ICMPD and IOM, 2015).

- Phase 2, the right of residence, entitles ECOWAS citizens to equal treatment when living or taking up employment in other Member States. This right has been largely achieved, though some countries continue to restrict employment in certain sectors for non-citizens and have not established clear guidelines for obtaining residence permits or work authorization (ibid).

- Phase 3, the right of establishment, gives ECOWAS citizens the right to carry out economic activities and set up enterprises in other Member States, but remains largely unfulfilled (ibid).

Measures such as the introduction of common ECOWAS travel certificates and passports have been implemented to support the Free MovementProtocols. Simplified border formalities have also been proposed but not yet realized in most countries. Full implementation of the Protocols remains hampered by limited harmonization of national laws with ECOWAS Protocols and policy (Awumbila et al, 2014).

Subsequent, non-binding strategic documents, such as the 2008 ECOWAS Common Approach on Migration, have reinforced the centrality of freedom of movement within ECOWAS, while at the same time broadening the scope of ECOWAS migration efforts to include coordination on migration to and from the bloc (Schöfberger, 2020).

These binding protocols and non-binding strategic documents provide ECOWAS with a mandate for harmonizing migration data collection and reporting systems within the sub-region. Although ECOWAS does not currently publish regular reports on migration data, several ongoing initiatives, such as FMM West Africa, and the Migration Dialogue for West Africa (see below), promote improving and harmonizing data collection and management in order to make regional migration data available for wider use.

The African Union has promoted freedom of movement throughout the continent since its foundation. Agenda 2063, adopted by Member States in 2015, includes commitments to increase integration through the establishment of visa-free regimes and the creation of an African passport. However, implementation of African Union migration policies remains slow. The 2018 Protocol on Free Movement of Persons in Africa, which includes binding commitments on freedom of entry, residence and establishment, has only been ratified by 4 of the 55 Member States as of late 2020.

The West African Economic and Monetary Union (WAEMU), which includes eight predominantly francophone countries, included provisions on freedom of movement, residence and establishment in its founding treaties (Schöfberger, 2020). As all WAEMU countries are also members of ECOWAS, work towards these rights has largely occurred within ECOWAS.

Regional Migration Dialogues:

- The Migration Dialogue for West Africa (MIDWA) is a regional consultative process on migration established in 2001 to promote cooperation on migration policies among ECOWAS member states and partners.

- Euro-African Dialogue on Migration and Development (Rabat Process) is an inter-regional forum bringing together African and European countries and regional organizations to address migration issues.

Further reading

International Organization for Migration

2021 A region on the move: Mobility trends in West and Central Africa, January - December 2021.

2020 Regional Mobility Mapping: West and Central Africa, June 2020

2019 Migration Data on the Central Mediterranean Route: What Do We Know? GMDAC Briefing Series: Towards safer migration in Africa: Migration and Data in Northern and Western Africa.

2018 Guidelines for the Harmonization Of Migration Data Management in the ECOWAS Region.

2008 Enhancing Data on Migration in West and Central Africa.

Africa Union

2020 Report on Labour Migration Statistics in Africa, Second Edition.

Regional Mixed Migration Secretariat (RMMS) West Africa

2017 Mixed Migration in West Africa: Data, Routes and Vulnerabilities of People on the Move.

International Centre for Migration Policy Development and International Organization for Migration

2015 A Survey on Migration Policies in West Africa.

Awumbila, M., Y. Benneh, J.K. Teye and G. Atiim

2014 Across Artificial Borders: An assessment of labour migration in the ECOWAS region. ACP Observatory on Migration.

1 As defined by the UN Statistics Division. Benin, Burkina Faso, Cabo Verde, Côte d’Ivoire, Gambia, Ghana, Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, Liberia, Mali, Mauritania, Niger, Nigeria, Senegal, Sierra Leone and Togo.

Back to top