Back to top

Definitions

International trade is commonly defined as the buying and selling of goods and services across international borders. The effect that international trade has on migration and vice-versa depends on several factors such as the type of origin country, the type of markets in the origin and destination countries, the type of immigrants, the size of the immigrant community in the host country, migration policies, bilateral trade agreements and tariffs.

Trade in services is the most dynamic segment of international trade in terms of growth and is defined in the General Agreement on Trade in Services (GATS) in terms of four modes of supply: cross-border, consumption abroad, commercial presence and presence of natural persons. Of these, Mode 4 “covers individuals travelling from their own country to supply services in another” (WTO, 2015) and can be related to labour mobility.

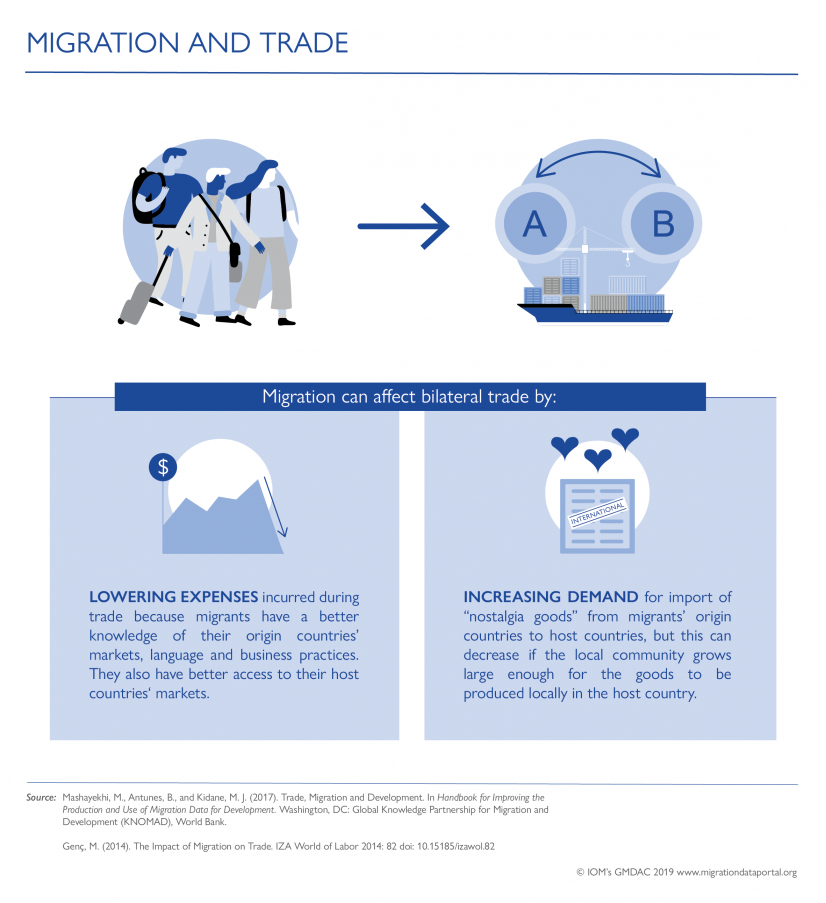

Migration is considered to affect bilateral trade in two main ways:

(1) Transaction cost effects: Migrants often have in-depth knowledge of their origin countries’ market, social and business networks, language and business practices. This knowledge, combined with the access they may have to their host countries’ market, can lower expenses incurred for both imports and exports.

(2) Immigrant preference effects: Immigrants’ demand for products from their origin countries increases imports of these “nostalgia goods” to the host countries. In the long run, these imports can decrease if the size of the immigrant community grows large enough for local firms in the host country to produce these goods.

The effect of migration on trade is often described in terms of the migrant elasticity of trade, which is the percentage change in trade caused by a one per cent increase in the stock of immigrants (Genç, 2014).

In economic terms, if an increase in migration leads to an increase in trade, they are considered complements. For example, if migrants lower the transaction costs of trade and raise the demand for nostalgia goods, they increase trade between their origin and host countries.

On the other hand, if an increase in migration leads to a decrease in trade, they are considered substitutes. For example, if more trade creates new employment opportunities and improves welfare outcomes in the migrants’ origin countries, fewer people may be inclined to leave.

A quantitative review of 48 studies between 1994 and 2010 shows that the majority of immigrant elasticities of trade were positive. The estimated immigration elasticities imply that, at a statistically significant level, a 10 per cent increase in the number of immigrants can cause trade to grow by 1.5 per cent on average (Genc, Gheasi, Nijkamp and Poot, 2012). For example, without accounting for unobserved factors before 2000, a 10 per cent increase in the number of immigrants are estimated to have caused exports from the United States of America to grow by 4.8 per cent and caused imports in Switzerland to grow by 3 per cent (ibid.). Migration and international trade are generally found to be complements (see forthcoming IOM paper by Cottier and Shinghal, 2019).

While both immigration and emigration appear to have a stable, significant effect on trade when they are studied at a specific point in time, migration appears to have a negligible effect on trade in the long term when unobserved bilateral ties are taken into account (Parsons, 2012). Analyzing the effects of migration on trade at the country-level shows that migrants can both increase and decrease trade (ibid.).

Bilateral trade is higher when the size of the inward migration corridor is larger (Fagiolo and Mastrorillo, 2014). Immigrants coming from third countries can also increase bilateral import flows when their countries of origin are high tariff protected (Figueiredo, Lima and Orefice, 2016). Additionally, a 1 per cent increase in immigrants causes firms in the host area to export 6 to 10 per cent more services to the immigrants’ origin country (Gianmarco, Peri and Wright, 2015).

Trade data are collected from both national and international sources. National reports and databases provide data on bilateral imports and exports while international organizations offer data that are comparable. The United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) collects and processes an extensive range of data from both national and international sources to study the interaction of trade and development. The World Trade Organization (WTO) brings together information on trade, market access and trade agreements. WITS (World Integrated Trade Solution), a software application developed by the World Bank in collaboration with UNCTAD and other organizations, compiles data on trade and tariffs.

Services trade data are also important to understand the effects of trade on migration and vice-versa. UN Service Trade, a database from the United Nations Statistical Division, offers data on services trade. The World Bank’s Export Value Added Database and the OECD/WTO Trade in Value Added (TiVA) database both provide data on trade in value added. The Manual on Statistics of International Trade (MSITS), compiled by the Interagency Task Force on Statistics of International Trade in Services, provides an internationally approved framework to expand the compilation and reporting of comparable statistics on international trade in services.

Data on immigrant stocks and diasporas are essential to understand the relationship between immigration and trade. The United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs (UN DESA) uses data from national statistics on country of birth or country of citizenship to provide global estimates of international migrant stocks.

Econometric studies from academia and international organizations compile the different types of data on trade and migration and compare them to study the relationship between these two intrinsic aspects of development.

Trade and migration as drivers of development lie at the intersection of several policy areas. Yet, data on these international phenomena lack the level of disaggregation required for evidence-based policy. At the regional and national levels, there are significant variations in data availability that lead to compilation issues. National differences in definitions of who is counted as temporary also lead to comparability issues.

Additionally, collection of trade data, in particular trade in services data is relatively new. Countries that began collecting data on trade in services according to the GATS modes of supply found that a single trade transaction can sometimes be a combination of modes, making data capture for a particular mode difficult (Mashayekhi, Antunes and Kidane, 2017).

Most older econometric studies use cross-sectional data (where the same trading partners were observed at a certain point in time) and therefore cannot account for unobserved factors – such as historical, cultural and political ties – in their comparisons (Parsons, 2012). Further, these studies do not use more sophisticated methods of analyses which can identify the causal impact and direction of causality of migration on trade (Genç, 2014). These studies also tend to lack data that are disaggregated at the skill level and occupation of the migrant stock, as well as data that assess the variety of traded goods and bilateral ties between the origin and destination countries, which are equally important factors for such studies (ibid.).

Further reading

| Bowen, H. P., and Wu, J. P. |

| 2013 |

Immigrant Specificity and the Relationship between Trade and Immigration: Theory and Evidence. Southern Economic Journal, 80(2), 366–384. |

| Campaniello, N. |

| 2014 |

The causal effect of trade on migration: Evidence from countries of the Euro-Mediterranean partnership. Labour Economics, 30, 223–233. |

| Cottier, T. and Shingal, A. |

| 2019 |

Migration, International Trade and Foreign Direct Investment in the 21st Century: Towards a new Common Concern of Humankind, IOM Paper, Forthcoming 2019 |

| Fagiolo, G., and Mastrorillo, M. |

| 2014 |

Does human migration affect international trade? A complex-network perspective. PLoS ONE, 9(5), 1–20.

|

| Figueiredo, E., Lima, L. R., and Orefice, G. |

| 2016 |

Third Country Effect of Migration: The Trade-Migration Nexus Revisited. CEPII Working Paper. |

| Genç, M. |

| 2014 |

The impact of migration on trade. IZA World of Labor 2014: 82 |

| Genç, M., Gheasi, M., Nijkamp, P., and Poot, J. |

| 2012 |

The impact of immigration on international trade: A meta- analysis. In P. Nijkamp, J. Poot, & M. Sahin (Eds.), Migration Impact Assessment: New Horizons (pp. 301–337). Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing Limited. |

| IOM, OECD and World Bank |

| 2003 |

Trade and Migration: Building Bridges for Global Labour and Mobility, OECD Publishing, Paris |

| Mashayekhi, M., Antunes, B., and Kidane, M. J. |

| 2017 |

Trade, Migration and Development. In Handbook for Improving the production and use of Migration Data for Development. Global Knowledge Partnership for Migration and Development (KNOMAD), World Bank, Washington, DC. |

| Mattoo, A. and Carzaniga, A. (Eds.) |

| 2003 |

Moving People to Deliver Services. Oxford University Press and World Bank, Washington, D.C. |

| Ottaviano, G., Peri, G., and Wright, G. |

| 2015 |

Immigration, trade and productivity in services. VoxEU -- CEPR Policy Portal. |

| Parsons, C. R |

| 2012 |

Do Migrants Really Foster Trade? The Trade-Migration Nexus: a Panel Approach 1960–2000. Policy Research Working Paper; No. 6034, World Bank, Washington, D.C. |

Back to top