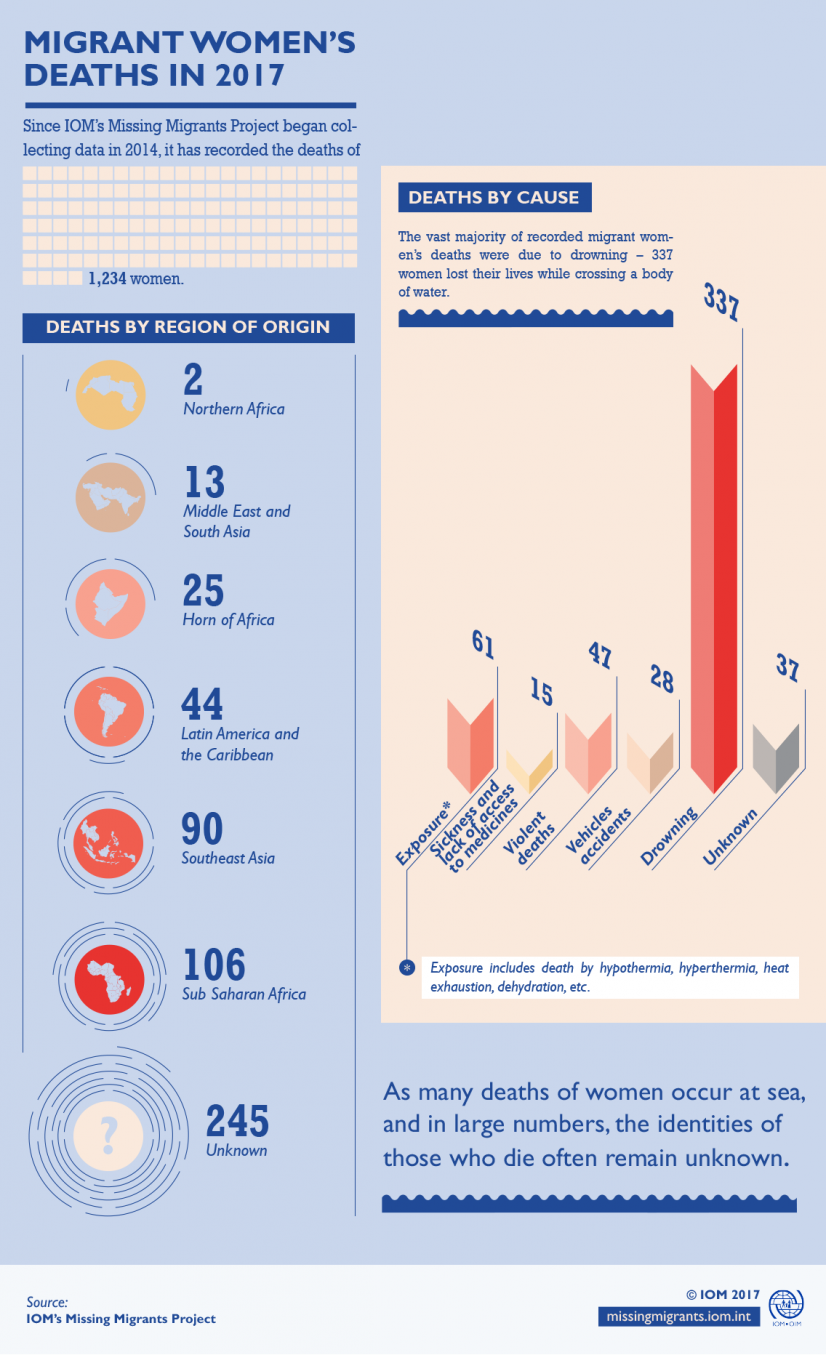

Since IOM’s Missing Migrants Project began collecting data in 2014, it has recorded the deaths of 1,234 women, more than half of whom died while attempting to cross the Mediterranean. This figure represents less than 5 per cent of the total number of migrant deaths recorded by IOM during this period. The real figure of migrant women who die is likely much higher, given that much of the most basic data are missing for those who died, especially regarding sex. Only 31 per cent of the incidents recorded by the Missing Migrants Project have any information on the sex of those who died or went missing.

A lack of reliable sex-disaggregated data perpetuates the invisibility of female migrant deaths. Information on the deaths of migrant women is highly contingent on the identification of bodies. As many deaths of women occur at sea, and in large numbers, the identities of those who die often remain unknown. Their remains are either not recovered from the water, or information about them is not reported by those managing the bodies. Other incidents occur in remote locations and mostly go unrecorded. When sources, such as medical examiners, NGOs, the media or other migrants report deaths, they usually just include the number of lives lost, which means that female migrants who die during their journeys may not be identified as such.

What the 2017 record tells us

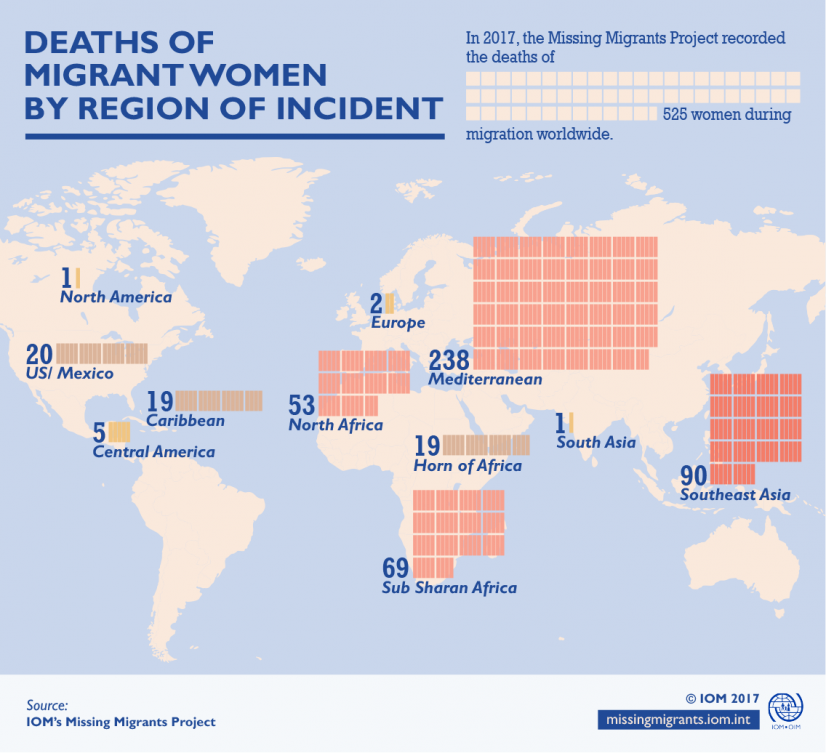

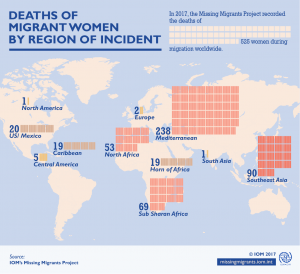

Nevertheless, records where the sex is known can provide insight on where and how women die crossing borders. Worldwide, the Missing Migrants Project recorded the deaths of 525 women during migration in 2017. Though the scarcity of sex-disaggregated data on migrant deaths means that it is difficult to say which migratory route is most dangerous for women, the available data indicate that crossing the Mediterranean is particularly deadly, with 238 confirmed women’s deaths last year. The Missing Migrants Project recorded 141 women who died while migrating in Africa, 90 who died in Southeast Asia and 20 while trying to cross the US-Mexico border in 2017.

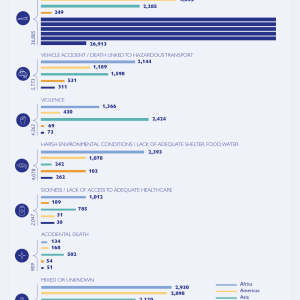

The vast majority of recorded migrant women’s deaths were due to drowning – 337 women lost their lives while crossing a body of water. The Mediterranean is not the only fatal sea journey location, as in 2017 79 women perished in the Bay of Bengal and the Naf River on the Myanmar-Bangladesh border.

The available data show that women are also undertaking dangerous journeys by land. In 2017, 61 women died due to exposure to harsh environments while migrating, 47 due to illness and lack of access to medicines, 28 due to vehicle accidents, and 15 suffered deaths due to violence. For 37 women, the cause of death is unknown.

Last year, 103 of the women recorded in the Missing Migrants Project database were originally from Asia, including the Middle East, while another 133 were from African nations and 44 were from the Americas. The origin of 245 others could not be determined.

Why women face higher risks

Evidence shows that women face greater risks of death while migrating irregularly. Many contributing factors for this exist, including gendered social practices within family groups and within countries of transit as well as smuggling practices.

In the Mediterranean, for instance, women and children are often placed below deck or in the middle of boats with the aim of protecting them during the crossing. However, this can lead to tragic consequences as it can be more difficult to escape if a boat is in distress. Search and rescue teams report finding women and children who could not escape fast enough and as a result suffocated from toxic fumes. Qualitative findings indicate that weaker swimming skills, heavier clothing and travelling with children may also lead to higher risks of drowning.

Even though women comprise a smaller proportion of the overall number of deaths than men, of the deaths recorded by Missing Migrants Project in 2017 the proportion of women who drowned was larger than the proportion of men who drowned: 64 per cent of the women who perished in 2017 drowned over a body of water, compared to 42 per cent of the men.

Globally, female migrants are at high risk of sexual abuse on their journeys. Research in Latin America showed that 60 per cent of women travelling irregularly through Mexico experienced sexual assault. When women become pregnant during migration, they have special health needs that often go unaddressed and can contribute to higher risk of fatality.

More about missing migrant women in 2017

Missing Migrants Project must rely on ad hoc media reporting and survivor testimonies to learn more about the women who left their homes searching for a better life and did not survive.

Below are some of the incidents recorded by MMP last year that involved women:

On 21 February, 2017, the bodies of three women and one man were recovered and another four women and four men remained missing after their boat sank off the coast of El Seibo Province, Dominican Republic. Two of the women who died were sisters Walkiria Matías Tapia and Yoleydi Matías Tapia, ages 17 and 19 and from Santo Domingo, and who, along with the other passengers, intended to reach Puerto Rico.

On 24 July, 2017, Rosa María de la Cruz Curruchich de Ortiz (age 37), Bernardo Ortiz de la Cruz (age 18), Florinda Manuel Pascal (age 17) and María Guadalupe Francisco Basilio (age 15) died trying to cross the Río Bravo, between Ciudad Juárez, Mexico, and El Paso, Texas, USA. Rosa and her son Bernardo travelled from their home in the rural municipality of Joyabaj, Guatemala, while Florinda and María came from San Miguel Acatán, Guatemala.

On 01 September, 2017, 26 Rohingya, including six women, six men, four girls and four boys died when their boat sank trying to cross the Naf River into Teknaf, Bangladesh. They were among the over 650,000 Rohingya who fled violence Rakhine State, Myanmar in the last five months of 2017.

On 03 November, 2017, 26 women from Nigeria, believed to be age 14 to 18 died in the Central Mediterranean. Another 53 people were estimated to have gone missing in this shipwreck. Autopsies revealed that two of the women were pregnant when they died. Only two of the women were identified before being buried after a funeral held in Salerno, Italy.

Making women more visible in an effort to stop migrant deaths

Recording information on people who die is only the first step to preventing more deaths in the future. More research on the reasons why women embark on migration journeys, and on the gendered dimensions of the risks that they face during these journeys is crucial to understanding how these deaths could have been avoided.

The stories of missing migrants are also about the families that are left behind, many who are mothers, wives and children. Few people undertake risky migrant journeys without the dream of supporting the lives of people back at home. What’s more, when a family member who migrated is not heard from again, this can have tragic effects that could be legal, economic, social and of course, painfully emotional. More support is needed for these families, including information about how to search for their loved ones.

Read more about migrant women deaths and missing migrants in the Fatal Journeys series.

Read more about the Missing Migrants Project methodology.