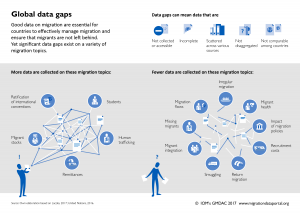

There are several references to migration in the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development (2030 Agenda), including Target 10.7 which calls for countries to “facilitate orderly, safe and regular migration through the implementation of planned and well-managed migration policies”. Meanwhile, the Sustainable Development Goals’ (SDGs) motto to “leave no one behind” is a clear call for sustainable development to be inclusive, including for migrants. While the inclusion of migration in the 2030 Agenda is a key opportunity to advance comprehensive migration governance, it also presents countries with a series of new data challenges and reporting requirements, as large amounts of migration-relevant data are required for SDG monitoring.

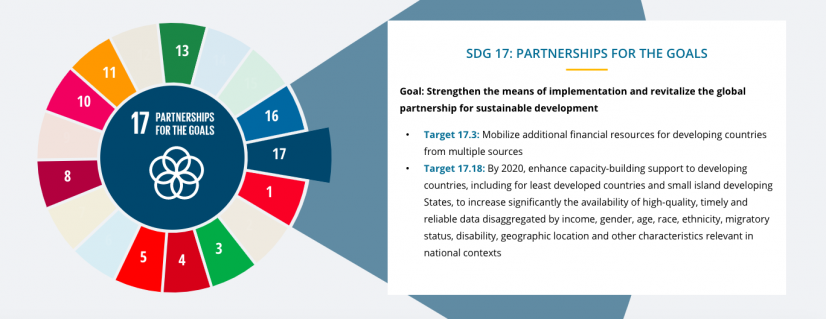

One specific challenge is the need to disaggregate indicators by migratory status. Target 17.18 calls for greater support to developing countries to increase significantly the availability of “high-quality, timely and reliable data, disaggregated by income, gender, age, race, ethnicity, and migratory status”. This call is part of a growing understanding that disaggregation is a crucial way to facilitate inclusiveness. There are many key dimensions of disaggregation, such as sex, age and disability, and disaggregation is one of nine pillars of the “data revolution”.

Disaggregation of data by migratory status can be a big challenge for National Statistical Offices (NSOs) around the world. This type of disaggregation is in many ways more challenging than others and it is made even harder thanks to the generalised lack of quality data on migration, as recognized most recently the Global Compact for Safe, Orderly and Regular Migration (GCM).

As countries monitor SDG indicators, levels of disaggregation of reported indicators by migratory status remains low.

This means that as we rapidly approach 2030 we still do not know what the effects of the SDGs are for migrants, and whether and to what extent they are being left behind.

Why?

With disaggregation, policymakers can look beyond averages in SDG data to study outcomes for migrants and track these over time. Disaggregation shows where interventions may need to target and reach migrants so that nobody is left behind, helping refine SDG programming. For example, disaggregation of indicator 3.1.1 (Maternal mortality ratio) would show whether migrant women may have a higher mortality rate than non-migrant women.

Beyond the SDGs, there is a paucity of data on migrant well-being and migrant integration in countries which disaggregation can help address. Disaggregated data are key to understanding migrants’ characteristics in health, education, employment and other areas, and comparing these to non-migrants’. Policymakers can examine whether and how any inequalities between these groups change over time, and explore possible reasons behind this. Such data can provide valuable evidence in topics from affordable housing to access to clean energy, enabling policymakers to treat migration as a cross-cutting theme when designing policies in these areas.

In other words, having disaggregated data across sectors would be a game-changer for migration policy, and in particular for mainstreaming migration.

Finally, disaggregated data could have value beyond national policymaking and the SDGs. The GCM is composed of 23 objectives on policy areas from decent work to access to basic services, yet has no follow-up and review framework. Having disaggregated data across policy areas would give policymakers a stronger evidence base on which to base many GCM interventions.

As the COVID-19 pandemic continues to expose and in many cases widen inequalities in society, migrants are often among the most affected. Many migrants are more vulnerable to COVID-19 due to factors such as differentiated access to healthcare services, support and information when compared to non-migrants. This highlights the importance of disaggregating data by migratory status to capture this and better target migrants in COVID-19 responses. Response programming should disaggregate data by migratory status as far as possible, always with necessary safeguards, which will also help policymakers consider the needs of migrants when turning to recovery policies. There is also a need as far as possible to disaggregate relevant migration data by age and/or disability, to identify migrants who may be subject to overlapping vulnerabilities in relation to COVID-19.

Traditional data collection around the world will be disrupted by the pandemic. This means that SDG monitoring will be impacted, in particular given many indicators are based on household surveys. To counter this, practitioners may explore the potential of leveraging new data sources for SDG indicators, including for migration-SDG data.

How?

In many ways, disaggregating data by migratory status can be more challenging than doing this by dimensions such as sex or age. Many migrants are part of hidden populations that are not easily counted, and the most vulnerable may rarely appear in official statistics. The general lack of quality migration data means that often, data on migrants are poorer than on other population groups to begin with.

Before embarking on a disaggregation exercise, there are many issues to consider. This includes specific challenges for different data sources. For example, as large sample sizes are needed for disaggregation it can be expensive to use household surveys. IOM GMDAC conducted a pilot study on disaggregating SDG indicators by migratory status based on harmonized census data for 73 countries. However, census data often takes years to be released before it can be analysed. As a result, NSOs may explore the potential of administrative data sources or census microdata for SDG data. There are challenges in defining disaggregation categories – some important concepts relevant to disaggregation lack internationally agreed definitions. Further, there are important considerations beyond data collection. For example, there may be a need for specialised awareness raising in NSOs on the importance of disaggregation in the first place, or for tailored approaches to disseminate disaggregated data to policymakers in the right ministries.

As the focus on disaggregation grows, guidance on some of the above topics has been developed. While this has been crucial, tools are not yet designed to fit individual country needs and capacities, and do not focus on providing step-by-step practical assistance. In response to this, in 2020 IOM’s Global Migration Data Analysis Centre (GMDAC) will produce user-friendly guidance on disaggregation of SDG indicators by migratory status.

Meanwhile, positive examples of disaggregation in action are emerging. For example, the Italian NSO (Istat) has taken steps to disaggregate several SDG indicators by country of citizenship, and further distinguish between first and second generation migrants by using categorisation from the Invalsi (National Institute for the Evaluation of the Education and Training system).

Call to action

Measuring the links between migration and development is challenging. Disaggregation brings to the table a solution to one part of this, which is to measure development outcomes on migrants themselves. Still, disaggregating data by migratory status can be challenging in practice. As efforts continue to develop relevant guidance for practitioners, many questions remain open.

All those working in disaggregation should partner as much as possible, including with countries’ NSOs and line ministries, to discuss experiences, good practices and lessons learned. In particular, examples of countries improving disaggregation at low cost will be useful going forward.

IOM aims to make progress on some of these challenges by developing guidance on disaggregation of SDG indicators by migratory status. In this way, IOM hopes to make migrants more visible in the road to 2030. We look forward to tackling this together.

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed in this blog are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the International Organization for Migration (IOM) or the United Nations. Any designations employed and the presentation of material throughout the blog do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of IOM concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area, or of its authorities, or concerning its frontiers and boundaries.