From destination country to one of origin

Traditionally, migration dynamics in South America are marked by intra- and extra-regional patterns, with the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela (Venezuela)1

among the countries of destination in the region—at least up until a few years ago.

Starting in 2010, the migration profile of Venezuela began shifting from a country of destination to a country of origin. Among the reasons for this shift or increase in emigration, are recent developments in the country, especially regarding its economic situation, food shortages, limitations in access to services such as health care, lack of cash and political polarization. In particular, in 2017 there was a significant increase in Venezuelans emigrating in record numbers to other countries within the region and the world. Not only has the emigration to traditional destinations intensified, but there has also been a diversification of destinations as Venezuelans emigrate to new countries.

The increased Venezuelan emigration has proved challenging for countries in the region. Some South American states have applied ordinary legal migration tools to grant Venezuelans (permanent or temporary) residence; several others have approved new legal measures since the beginning of 2017 to receive Venezuelans. Such responses highlight the importance of countries’ migration governance to adapt in times of increasing immigration.

In addition to legal tools, responses also include the creation of new data-gathering tools. For example, the Colombian Government recently announced the creation of the Administrative Registry of Venezuelan Migrants (RAMV in its Spanish acronym), which is an innovative mechanism supported by IOM to gather information on Venezuelan migrants in irregular conditions in order to design and implement public policy on immigration. As of 14 April, more than 63,329 persons have been registered in the RAMV.

Additional regional responses include IOM’s Action Plan, which among other activities, calls for better data collection and dissemination, capacity building and coordination to respond to the needs and priorities expressed by Governments and the information gathered through IOM’s Displacement Tracking Matrix (DTM). DTM is a strong tool to capture, process and disseminate information in order to provide a better understanding of the movements and evolving needs of the Venezuelan nationals in the region. Enhancing DTM field work and data analysis capacity in the region will provide Governments with reliable and comprehensive information on recent flows.

The numbers tell the story of the extent and nature of Venezuelans’ emigration, as well the nature of the region’s response.

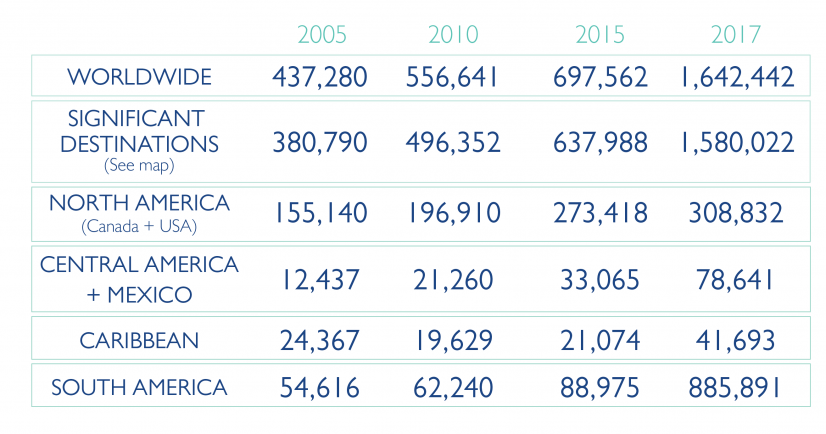

Estimates of Venezuelans living abroad and top destinations

While there are challenges due to data and information gaps, there is clear evidence of a continued large-scale migration as indicated by a significant increase of Venezuelan nationals abroad. Globally, the number of Venezuelans abroad rose from 700,000 to more than 1,500,000 between 2015 and 2017, which represents an increase of nearly 110 per cent. In South America, the number of Venezuelans rose from 89,000 in 2015 to 900,000 in 2017, an increase of approximately 900 per cent.

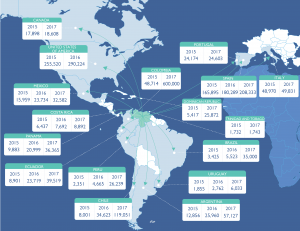

Estimates of Venezuelan migrant stocks in selected countries

Source: Official sources and own estimates (Map). UNDESA 2005, 2010; UNDESA and other estimates 2015, 2017 (Table) .

Note: The 2017 figures accumulate the latest data available in every country.

The top countries of destination for Venezuelans are Colombia (600,000), the United States of America (290,000) and Spain (208,000). Among other reasons, these are the top countries of destinations because: the United States provides labour market opportunities for skilled and professional Venezuelans; Spain provides legal channels for citizenship for Venezuelans with Spanish ancestry; and Colombia’s proximity and policies, such as those on family and residency, facilitate Venezuelan immigration. These countries together account for about 68 per cent of the one and a half million Venezuelans abroad. It is interesting to also note that in Spain, the number of women (113,292) is larger than that of men (95,041). Additionally, more than 60 per cent (127,825) of Venezuelans in Spain have Spanish citizenship, related to the previous Spanish emigration towards Venezuela.

The figures above, which also appear in IOM’s latest report about Venezuelans in other countries are derived from: 1) census data and 2) administrative records such as those on residence. These official sources, however, allow us to provide only estimates. Likewise, due to limited data sources, it is difficult to quantify irregular migration as well as a transit population. The nature of the migration phenomenon, which is changing and mobile, and limited existing tools in States to measure migration add to the difficulties of measuring the complexity of migration.

Diversification of countries of destination

In the last two years, a growing rate of Venezuelan nationals in South American countries has been recorded, along with a diversification of countries of destination. Chile, Argentina, Ecuador, Brazil, Peru and Uruguay are all new destination and non-border countries where the number of Venezuelans has increased. Among these new destinations, Chile experienced the largest increase in relative terms between 2015 and 2017. In April 2018, Peru reported an estimated 200,000 Venezuelan nationals in its territory. The number of Venezuelans has also increased in the border countries of Colombia and Brazil.

Although Colombia remains the main destination for Venezuelans in South America, a large percentage of Venezuelan citizens enter Colombia in transit towards third destination countries. This dynamic has increased in recent months.

There has also been a diversification towards other destination countries in Latin America. Among others are Mexico, Panama, Costa Rica and the Caribbean Islands. Recent information released in the Second National Immigrant Survey 2017 (ENI in its Spanish acronym), conducted by the National Statistics Office of the Dominican Republic, indicates that Venezuelan immigration increased from 3,434 people in 2012 to 25,872 in 2017; this represents a 653 per cent growth. Other Caribbean Islands such as Aruba, Curaçao and the Republic of Trinidad and Tobago have also recorded an increasing number of Venezuelans. The short distance from these Islands facilitates Venezuelan’s mobility.

New legal tools for Venezuelan immigration

Between 2015 and 2017, more than 400,000 (temporary and permanent) residence permits were issued to Venezuelan nationals by ordinary and extraordinary legal measures. The following countries approved specific legislation to issue residence permits to Venezuelans:

- Colombia — “Special Permit of Permanence” (2017)

- Peru — “Temporary Residence Permit” (2017)

- Ecuador — “Ecuador-Venezuela Migration Statute” (2011) and “UNASUR Visa” (2017)

- Argentina — applying the "MERCOSUR Residency Agreement” (2009) to Venezuelan nationals

- Brazil — “Temporary Permit” (2017)

- Uruguay — applying the “MERCOSUR Residency Agreement” (2009) and Permanent Residence through National Law (2014) to Venezuelan nationals

- Chile — Democratic Responsibility Visa (announced in April 2018)

It should be noted that while some States apply the MERCOSUR Residency Agreement, which provides temporary and optional permanent residency to nationals of MERCOSUR Member and Associate Member States if they meet certain criteria, Venezuela has not ratified the agreement.

Other South American countries issue residence permits to Venezuelan nationals only through the ordinary channels of regularization. In this sense, the number of residence permits issued by Chile is noteworthy, reaching about 120,000 between 2015 and 2017.

IOM commends all countries in the region that have adopted and implemented migration instruments that have facilitated access to rights for Venezuelan nationals.

Diverse migration routes

The diversity of routes used by Venezuelans shows a dynamic and changing mobility. Apart from the air route, the land and maritime routes have recently become more significant. In the case of neighbouring Caribbean islands, such as Aruba, Bonaire, Curaçao, and the Republic of Trinidad and Tobago, the short distances facilitate maritime mobility. In the case of Colombia and Brazil, the main part of the movement is by land across the border. In Colombia, the largest number of entries is registered in the city of Cucuta. In Brazil, the highest number of entries by Venezuelans is registered in the state of Roraima. Numerous entries by Venezuelan nationals into Ecuador are also registered through Rumichaca; into Peru through Tumbes (border with Ecuador); and into Chile through Tacna (border with Peru), to give some examples.

Heterogenous profile of Venezuelan migrants

Indigenous populations, women, unaccompanied children and adolescents have been identified as highly vulnerable groups among the migrant population. In Brazil, the presence of the indigenous Warao people has been observed, with an increase seen in 2017, particularly in the States of Roraima (RR), Amazonas (AM) and Pará (PA). Estimates in January 2018 from the National Human Rights Council show that around 370 indigenous Warao are sheltered in BoaVista; another 370 are in Pacaraima (RR); 150 in Manaus (AM);110 in Santarém; and 100 Belém (PA).

Migrants face vulnerabilities particularly related to health and are at risk of human trafficking or smuggling. They also face difficulties and many challenges in some urban areas related to labour market insertion. In addition, a significant proportion of Venezuelan migrants have a good level of education and intend to continue their studies in host countries (i.e. Argentina), and get well remunerated jobs or set up their own businesses (i.e. Argentina, Uruguay and Chile). However, some of them are exploited, in part, due to the lack of skills recognition and their legal status, among other reasons. Indeed, some Venezuelans nationals remain in an irregular situation due to high fees, lack of documentation requirements and long bureaucratic waiting periods, among other reasons. This vulnerability could lead to exploitation, violence, and human trafficking, among other risks.

According to initial IOM DTM results in Peruvian border areas (Tumbes and Tacna), Venezuelan migrants are mainly young, professional (from 18 to 35 years of age) and mostly single; there is a greater proportion of males (63%). A significant number of those surveyed have children, most of them in Venezuela. In contrast, according to Guyana DTM results, there is a greater proportion of females (60%), and a small percentage of children (3%).

Also, according to surveys (DTM and others), in some countries (i.e. Peru, Brazil, Ecuador and Colombia) there were xenophobic attitudes towards Venezuelans citizens, especially towards those who have less education and work in the informal labor market.

The future

In general, Venezuelan’s immigration has been well received and States have made great efforts to solve challenges arising from increased numbers of migrants. For example, the special legal measures some South American countries have taken to welcome them indicate countries’ willingness to integrate Venezuelans into social life and leverage their abilities and experiences to build strong multicultural societies. It is possible that the social inclusion process of Venezuelan migrants implies that local communities and authorities will need to take further action to develop, for example, labor orientation, documentation guidance, educational procedures, and socio-cultural integration activities. Besides, it remains unclear if and when Venezuela’s economic and social situation will improve and how many more people will emigrate. For now, the scale of Venezuelan immigration to countries in South America and the rest of the world shows no signs of slowing.

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed in this blog are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the International Organization for Migration (IOM). The designations employed and the presentation of material throughout the blog do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of IOM concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area, or of its authorities, or concerning its frontiers and boundaries.

- 1The Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela is the country's official name, but readability only the first reference of the country will include the official name.