With the onset of the conflict in Yemen, experts anticipated that the number of migrant arrivals in Yemen would significantly decrease. However, the number of migrant arrivals in Yemen is projected to increase by 50 per cent by the end of 2018 compared to 2017. This means that the number of migrant arrivals via the Gulf of Aden to Yemen is expected to exceed the annual number of irregular arrivals in Europe via the Mediterranean Sea, the migration corridor with the most documented migrant deaths (IOM, 2018). Additionally, between 2010 and 2017, intra-African migration had the largest average annual increase in the number of international migrants (UN DESA, 2017). What is driving this unexpected increase in regional migration and the spill-over into the Arabian Peninsula?

The remainder of this post draws from IOM’s A Region on the Move: Mid-year Trends Report –January to June 2018 and IOM GMDAC’s Data Bulletin Series: Informing the Implementation of the Global Compact for Migration.

The push factors behind the shift

The majority of migrants on the Gulf of Aden-Yemen/Saudi Arabia route who were interviewed by the Mixed Migration Centre (MMC) were Ethiopians and Somalians (Horwood, Forin and Frouws, 2018). Environmental problems and economic factors, often aggravated by conflict, have led people to move. A severe drought that ended in 2017 followed by heavy floods in 2018 triggered the internal displacement of 289,000 people in Somalia (IDMC, 2018). 341,000 Somalians were newly displaced due to conflict and violence in the first half of 2018 (ibid.). As of October 2018, an estimated 551,000 Somalians were refugees in neighbouring countries (UNHCR, 2018). For a period of five years from 2013 , the Government of Ethiopia had banned low-skilled migration to GCC countries which could have also indirectly increased the number of people relying on irregular migration channels (ILO, 2016; 2017).1

A combination of environmental factors and intercommunal violence newly displaced 1,562,000 Ethiopians in the first half of 2018 within the country (IDMC, 2018). The factors behind such ongoing movement and displacement in the region, if not resolved, have the potential to trigger further movements across borders in search of livelihood options.

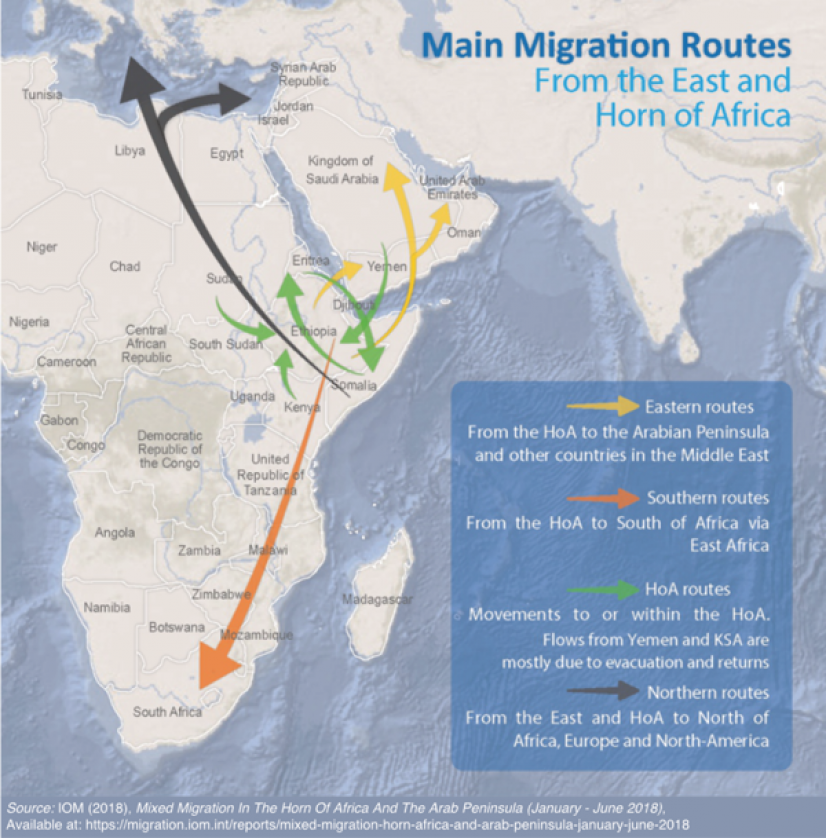

IOM’s Displacement Tracking Matrix uses flow-monitoring points (FMPs) to collect data on movements of populations at entry, transit and exit points. Of the 444,490 migrant observations recorded in Djibouti, Ethiopia, Somalia and Yemen in the first half of 2018, 45 per cent indicated that they were migrating within the Horn of Africa, 43 per cent on the Eastern route, including Yemen, the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia and other Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries, 8 per cent along the southern route and 5 per cent along the northern route (IOM, 2018).2

Migrants from the Horn of Africa often make the perilous journey to Yemen in hopes of continuing eastwards and finding asylum or stability in GCC countries. 50,339 new migrant arrivals were observed in the first half of 2018 (ibid.).3

Two important questions are: What is the international community doing to address the specific challenges of this shift? How can data be used to ensure safe and dignified migration in this corridor?

What is the international community doing?

On 7 December 2018, IOM co-hosted a conference in Djibouti to address the humanitarian needs of migrants in the Horn of Africa, Yemen and GCC countries. Humanitarian organizations and delegates from seven countries – Djibouti, Egypt, Ethiopia, the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, Somalia, and Yemen – agreed to address the issues by focusing on six key areas.

How can data be used to ensure safe and dignified migration?

For most of the solutions proposed in the conference, data are important to make informed decisions and measure impact. The following paragraphs highlight 3 ways data can improve the protection response:

Ensuring humanitarian access: Humanitarian organizations require data to assess changing trends and be prepared to offer timely assistance. For example, the IOM’s Displacement Tracking Matrix (DTM) collects information on migratory patterns by tracking mobility, monitoring flows, and administering surveys. Knowing the demographics of the migrants also helps identify their vulnerabilities and respond appropriately. Located along the migratory routes, IOM’s Migrant Response Centres (MRCs) register migrants and provide multifaceted support to stranded migrants. Data collected by MRCs also offer insights on the profiles of migrants using the eastern route. Further cooperation of national and international agencies as well as integration of their data can improve access to vital information.

Holding smugglers and human traffickers accountable for abuses inflicted on migrants: Even though the anti-trafficking movement has gained momentum at the global level, large gaps exist in data on human trafficking and migrant smuggling. The IOM’s Counter Trafficking Data Collaborative (CTDC) and UNODC’s Global Report on Trafficking in Persons 2016 are few examples that make data publicly available, but more work is required in the anti-trafficking community to standardize the collection and sharing of data. Estimating the risks of human smuggling for irregular migration based on disaggregated data can help mitigate the risks for more vulnerable groups such as women and children. According to Reitano and Kaysser, measuring the number of migrants using smugglers, the size and value of the migrant smuggling market as well as the level of criminal consolidation in the market can also be valuable for policymakers.

Enhancing safe, dignified and voluntary return and sustainable reintegration: Financial and logistical assistance are often helpful for irregular migrants who would like to leave voluntarily, but lack the means to do so. Well-managed Assisted Voluntary Return and Reintegration (AVRR) programmes can ensure the safe, dignified and voluntary return of irregular migrants. At the same time, countries that plan to implement AVRR programmes need reliable data to assess the requirements and to consistently evaluate the sustainability of the returnees’ reintegration in terms of establishing self-sufficiency and meaningful socioeconomic impact.

The meeting of central political and humanitarian agencies in Djibouti to address this dramatic shift is an important step, but not an end in itself. Policymakers need reliable and comparable data to better understand the scope and implications of the irregular migration via the Gulf of Aden to Yemen. This, in turn, will support evidence-based policies to save migrant lives as well as encourage regular and well-managed migration.

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed in this blog are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the United Nations or the International Organization for Migration (IOM). The designations employed and the presentation of material throughout the blog do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of IOM concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area, or of its authorities, or concerning its frontiers and boundaries.

- 1The Government of Ethiopia lifted the ban in early 2018.

- 2Different Flow Monitoring Points can ‘observe’ the same migrant multiple times.

- 3The number is significantly lower than the number of migrants observed in Djibouti, Ethiopia, Somalia and Yemen who had indicated their intention to reach the Arabian Peninsula. This is due to the operational limits in monitoring activities caused by the ongoing conflict. See this DTM report for more details: https://migration.iom.int/reports/mixed-migration-horn-africa-and-arab-peninsula-january-june-2018