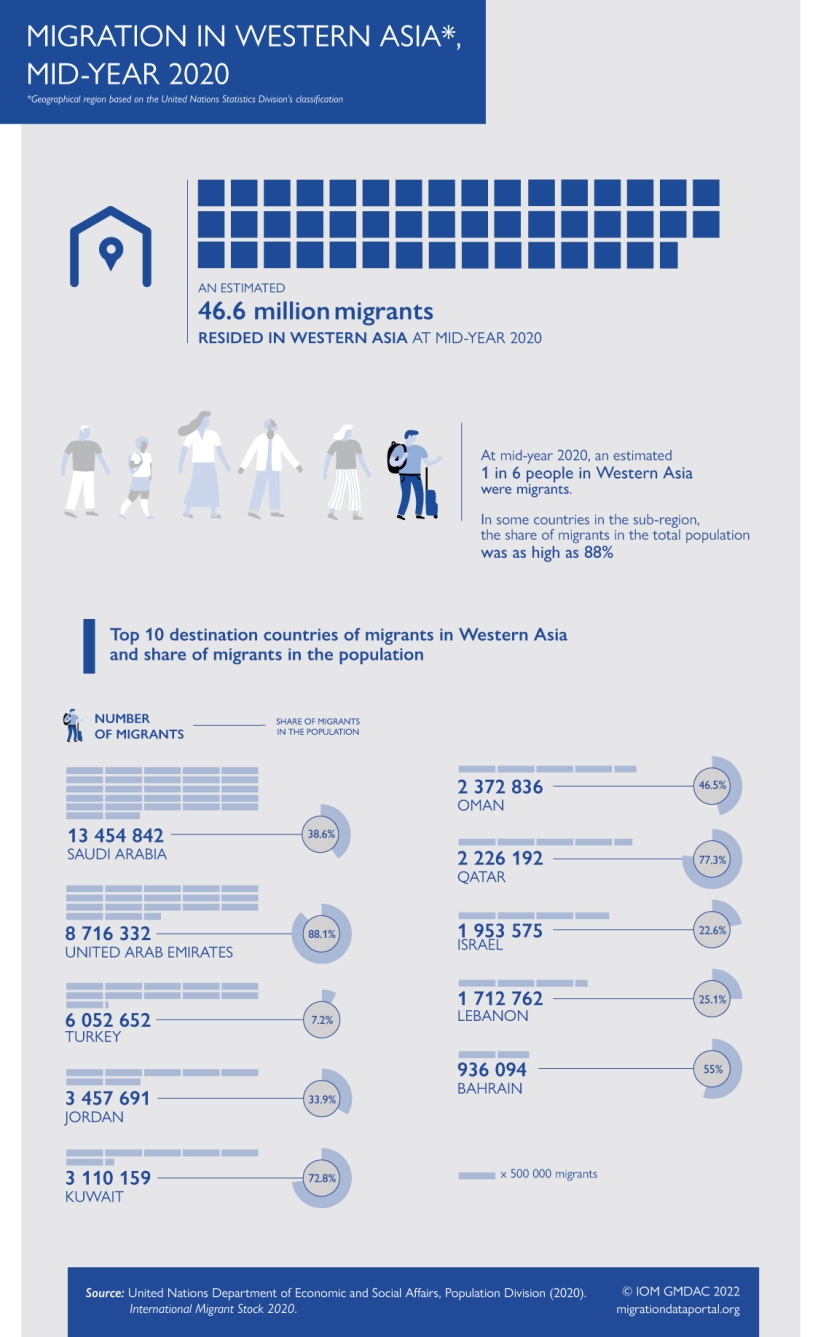

Migration data in Western Asia

Mobility in Western Asia1 has deep historical roots, and it has also witnessed a lot of voluntary and forced migratory movements in the past century. The economic and political diversity in the sub-region have led to it being home to some of the largest migrant populations as well as the largest and most protracted displacement situations globally. The surge in employment opportunities in the six Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC)2 countries following the oil booms attracted millions of labour migrants from within and outside Western Asia. As a share of the total population, the GCC countries continue to host the highest shares of migrants in the world. In addition to millions of Internally Displaced Persons (IDPs) hosted in Western Asia, the subregion also hosts high numbers of refugees. The country hosting the highest number of refugees (Turkey) as well as the country of origin of the highest number of refugees (Syrian Arab Republic) are both in the sub-region.

Recent trends

COVID-19:

- West Asian countries resorted to complete and partial restriction measures on mobility as a result of the pandemic. Airports in the GCC were mostly closed except for emergency and humanitarian flights. The GCC also maintained the closure of blue and land border points until September 2020, while the five Unofficial Ports of Entry on Yemeni coasts remained open (IOM, 2020a). Though 2021 witnessed a wide resumption of full operation of airports except in Oman and Yemen (IOM, 2021), a slight increase of mobility restrictions was recorded in January 2022 at several Points of Entry in countries across the subregion, especially for seaports (IOM, 2022a).

- However, COVID-19 mobility restrictions significantly impacted migration flows from the Horn of Africa to Yemen, reducing arrivals by 73 per cent in 2020 compared to the same period in 2019. By the end of September 2020, it was estimated that at least 14,500 migrants from the East and Horn of Africa were stranded in Yemen, while another 20,000 migrants were in need of assistance in Saudi Arabia (IOM, 2021b). It is estimated that 17,796 Yemenis returned from Saudi Arabia during the fourth quarter of 2021, adding to a total of 27,845 Yemenis who returned to Yemen in 2021 (IOM, 2022c).

- Many migrant workers who lost their jobs due to the pandemic were stranded due to the suspension of commercial flights, and several countries organized repatriation flights to assist their return. India -- the country of origin of the highest number of migrants in Western Asia -- organized an official repatriation operation and as of 30 April 2021, had facilitated the return of more than 6 million citizens, 61 per cent of whom were from West Asian countries (Indian Ministry of External Affairs, 2021).

- In Lebanon, the pandemic further aggravated the economic and political situation and drove an estimated 1.1 million refugees and Internally Displaced Persons (IDPs) into poverty. Similar increases in poverty levels were also noted among Syrian refugees in Jordan and the refugees/IDPs in Iraq’s Kurdish region, where the basic livelihoods of more than 62 per cent of the refugee population in the latter has been affected. Additionally, refugees have reported an increase in child marriages, child labour and domestic violence. (World Bank and UNHCR, 2020).

For an overview of migration data relevant to COVID-19, visit this page.

HOST COUNTRIES: Saudi Arabia (13.5 million), the United Arab Emirates (8.7 million) and Turkey (6.1 million) were estimated to be the three countries hosting the highest number of international migrants in the subregion as of mid-year 2020. Globally, Saudi Arabia hosts the third highest migrant population (UN DESA, 2020).

DESTINATION COUNTRIES: More than 56 per cent of all migrants from West Asian countries lived in other countries within the subregion (GMDAC analysis based on UN DESA, 2020). The highest number of emigrants from West Asian countries were estimated to live in Turkey (4 million), Jordan (3.2 million) and Germany (3 million) as of mid-year 2020 (UN DESA, 2020).

Labour migration:

Migrant workers constituted an estimated 41.4 per cent of the labour force in the Arab States in 2019. This share is the highest globally and is significantly higher than the global average of 4.9 per cent. However, at below 20 per cent, the Arab States also have the lowest share of females among migrant workers (ILO, 2021).

Remittances:

Lebanon was the highest recipient of remittances in the subregion (an estimated 6.6 billion USD) in 2021, contributing to a critical 34.8 per cent of its Gross Domestic Product (GDP). As a share of GDP, Lebanon is also the third top recipient of remittances globally. Jordan’s 3.6 billion USD remittances also amounted to 8 per cent of its GDP. However, both countries, along with Iraq, witnessed declines in remittance inflows in 2020 due to the impact of COVID (World Bank, 2021).

An estimated 17 per cent of all remittances sent globally in 2020 were from Western Asian countries (GMDAC analysis based on World Bank, 2021). Globally, the second and third highest amounts of remittances were sent from the United Arab Emirates and Saudi Arabia. Remittance outflows from the UAE decreased from 45 billion USD in 2019 to 43.2 billion USD in 2020, while the outflows from Saudi Arabia increased from 31.2 billion USD in 2019 to 34.6 billion USD in 2020 (World Bank, 2021).

Refugees:

At the end of 2020, an estimated 11.9 million refugees and asylum seekers3 were hosted in Western Asia. Turkey hosted 3.7 million refugees and was the top refugee-hosting country globally for the sixth year in a row. Other countries in the region hosting sizable refugee populations under the mandates of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) and The United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East (UNRWA) in 2020 were Jordan (more than 3 million) and Lebanon (nearly 1.4 million), (UNHCR, 2021a; UNRWA, 2021).

Internal displacement:

In Western Asia, an estimated 2.4 million people were newly displaced within their countries in 2020 and by the end of 2020, an estimated 14.2 million people were living in displacement in the subregion. The Syrian civil war, now in its tenth year, triggered an estimated 1.8 million new internal displacements in 2020, including 960,000 displaced by an offensive in Idlib that marked the largest displacement event since the beginning of the war. By the end of 2020, around 6.6 million people who were displaced due to conflict and violence in the Syrian Arab Republic over the years continued to live in internal displacement, the highest figure globally (IDMC, 2021).

Migrant deaths

IOM’s Missing Migrants Project (MMP) has recorded more than 47,000 fatalities during migration worldwide from January 2014 until January 2022. Almost half (over 23,800) of the recorded fatalities occurred in the Mediterranean Sea, deeming it the deadliest region for migration in the world. From 2014 to 2016, migrants who originated from Western Asia comprised the second largest population group who died while crossing the Mediterranean Sea.

Past and present migration patterns

The 1930s to the 1970s:

- The discovery of oil in the six Gulf countries between 1932 and 1967 resulted in massive capital accumulation. An acute shortage in the matching industrial labour prompted the Gulf countries to resort to recruiting workers from Iran, Western countries, and the Indian subcontinent. However, the independence of India in 1947 and the 1948 Arab-Israeli War increasingly shifted the recruitment patterns towards Arab workers (Fargues and De Bel-Air, 2015).

- The largest groups seeking better employment in the Gulf countries, mainly in Saudi Arabia, were Yemenis and Egyptians. Later waves of Arabs arriving in the Gulf countries included Palestinians and some Iraqis following the 1968 coup. There were also migrant labourers from the Arab Peninsula, particularly Omanis. Most migrants from the Mashreq countries resorted to the GCC with the exception of Iraq, which itself was a major importer of foreign labor as an oil-producing country (Kapiszewski, 2004).

1973-1990:

- As all Gulf states had achieved political independence in 1971, the Arab-Israeli war of 1973 additionally prompted a new phase of pan-Arab migration to the region. Arabs constituted up to 90 per cent of foreign workers in Saudi Arabia until the late 1970s. In 1973, an economic boom as a result of the shock in oil prices incited an enormous demand for migrant labour, increasing foreign populations by tenfold in just 15 years. Massive flows of labour migrants from Yemen, Egypt, Sudan, Jordan (both an origin and destination country itself), Pakistan and India were employed through the kafala system. As the only employment pathway in the GCC, a kafeel (sponsor) is the agency, company or private citizen who issues the employment contract. They bear full economic, social and legal responsibilities during the entire employment period and set the employment conditions, creating a dependency between the foreign worker and the kafeel (Fargues and De Bel-Air, 2015).

- Jordan is both a country of origin and destination of migrants. Most labour migrants from Jordan go to the GCC states and contribute to most remittances received in Jordan. When the Kingdom faced serious labour shortages during the 1970s and 1980s, it resorted to foreign labour particularly from Egypt and Syria, and later from other Asian countries (Khouri, 2004).

The 1990s:

- As a result of tensions following the 1990 Iraqi invasion of Kuwait, around three million immigrants were forced to leave their host countries in the Gulf. 350,000 Jordanians and Palestinians were evicted from Kuwait. Most of the Palestinians who left Kuwait went to Jordan. About 800,000 Yemenis returned from Saudi Arabia, exacerbating poverty in Yemen. During the same period, around two million Iraqi Shias and Kurds fled the Iraqi regime repression whereby many ended up internally displaced. The ensuing political and economic concerns also inspired a major shift in the national policies of Gulf states. By 1996, the share of Arabs in the GCC foreign population declined from 72 per cent in 1975 to only 31 per cent. (Shah, 2004)

- Lebanon is known for its sizable emigrant population whose remittances have provided significant support to the economic growth of the country. Since the 1990s, Egyptians and East Asians have largely contributed to replacement migration in Lebanon, whereby immigrants offset the national population decline in key sectors. On the other hand, many native skilled workers and professionals returned to Lebanon in the mid-1990s due to the decline of opportunities abroad or to partake in the attractive emerging reconstruction opportunities back home. By 2004, it was estimated that the Lebanese diaspora constituted 14 million nationals, four times the size of the population at home (Khouri, 2004).

- During 1990-2000, the Palestinian Territory – Jordan migration corridor was the fourth busiest corridor in the decade, which can be attributed to a large wave of Palestinian returnees from Gulf countries following the Gulf War (UN DESA, 2019).

- Until the late 1980s, most migrants arriving in Israel were of Jewish origin under the auspices of the 1950 Law of Return that grants Israeli citizenship to immigrant Jews and their children. However, since the 1990s, there has been an increase in non-Jewish migrants, primarily from the former Soviet Union and Ethiopia, based on the 1970 amendment of the Law. They were also joined by temporary labour migrants from Asia who were recruited to replace Palestinian workers, and later by asylum seekers from Sub-Saharan Africa who irregularly crossed the Egyptian border (MPI, 2020).

The 2000s and beyond:

Immigration

- The majority of migrants in Western Asia as of mid-year 2020 were from Asian countries. In terms of subregions, they were from Southern Asia, Western Asia and South-Eastern Asia (UN DESA, 2020).

- At the beginning of this century, non-nationals in the GCC countries made up around 70 per cent of the total labour force. Since the 1990s, a major change in the nationality composition of migrants to the Gulf occurred where Asian workers increasingly replaced Arabs for various social and political reasons (Kapiszewski, 2004).

- As of mid-year 2010, three of the top ten bilateral migration corridors between South Asian countries and oil producing countries in Western Asia. India – UAE corridor came in second, while the ninth and tenth were Bangladesh-UAE and India-Saudi Arabia, respectively (UN DESA, 2019b). During 2010-2019, the India-Saudi Arabia corridor jumped to the seventh place while the India – Oman corridor ranked eighth

- An agreement in 2011 between Ethiopia and Saudi Arabia resulted in a steep increase in the number of regular migrants to Saudi Arabia. However, it is estimated that they represent only 30-40 per cent of all Ethiopians in the Gulf, indicating that the remaining 60-70 per cent of Ethiopian migrants have irregular status (Fernandez, 2017).

- By 2014, the GCC emerged as the third largest host region for migrants and a major remittance-sending region, mostly directed to India, Pakistan, and Egypt (GCC’s top countries of origin). Irregular migrants also exceeded five million in Saudi Arabia as estimated by national authorities in 2012 (Fargues and De Bel-Air, 2015). The GCC countries have the highest ratio of foreign residents in the world, representing a large majority of the labor force. For example, in Qatar, foreigners occupied more than 99 per cent of the private sector labour force (Thiollet, 2016).

- As of mid-year 2020, women constituted only 35.3 per cent of the total migrant population in Western Asia, which is the lowest for any region in the world. The proportion of female migrants in the subregion ranged from 16.4 per cent in Oman to 59 per cent in Armenia. The share of female migrants in Armenia was not only the highest in the subregion but also the seventh highest globally (ibid.).

Emigration

- More than 56 per cent of all migrants from West Asian countries lived in other countries within the subregion (GMDAC analysis based on UN DESA, 2020). The highest number of emigrants from West Asian countries were estimated to live in Turkey (4 million), Jordan (3.2 million) and Germany (3 million) as of mid-year 2020 (UN DESA, 2020).

- Several West Asian countries are known for their large emigrant populations abroad in comparison to their total populations. There were an estimated 958,190 Armenian emigrants, 1,163,922 Azerbaijani emigrants and 861,077 Georgian emigrants at mid-year 2020 (UN DESA, 2021b). Most emigrants from these three countries (55% of Armenian emigrants, 65.8% of Azerbaijani emigrants and 52% of Georgian emigrants) resided in the Russian Federation alone. On the other hand, among the estimated 856,814 Lebanese emigrants at mid-2020, the majority resided in Saudi Arabia (153,988) followed by the U.S. (119,145). A significant number of Lebanese emigrants also resided in various European countries (248,537) (ibid). However, scarce data on emigration and diaspora studies show that the figures could be much higher.

- The 2002 Georgia Census shows that the country lost almost 20 per cent of its population to emigration from 1989. According to data by the National Statistics Office of Georgia for the past four years, the largest number of Georgian emigrants was recorded in 2018. Since the introduction of visa-free travel to EU/Schengen countries, the number of Georgian visas and residency permits (for labour and family reunification) have significantly increased, but a record number of refusals at the border were registered in 2018, especially in Germany, Greece, France, Cyprus and Poland. There has also been a rapid increase in the number of asylum requests by Georgian citizens, but the majority were rejected (State Commission on Migration Issues, 2019).

Refugees and asylum seekers

- In 2007, the Syrian Arab Republic hosted around 1.5 million Iraqi refugees fleeing the volatile situation in the country, deeming it the second largest refugee host country globally at the time. Jordan also received around 500,000 Iraqi refugees during that period (UNHCR, 2008).

- By the end of 2020, as a result of the ongoing Syrian war, the Syrian Arab Republic shifted from a major refugee hosting country to being the world’s largest country of origin of refugees for the seventh year in a row. A record high of 6.7 million Syrian refugees were hosted by 128 countries worldwide and more than six million IDPs lived in the Syrian Arab Republic as of 31 December 2020. The vast majority of Syrian refugees (more than 80%) remained in neighboring countries. Turkey continued to host the largest number of Syrian refugees (3.6 million), which is 92 per cent of its entire refugee population and 15 per cent of the global refugee population followed by Lebanon (865,531), Jordan (661,997), Iraq (242,163) and Egypt (130,577). Lebanon hosted the second largest number of refugees relative to its population globally (1 in 8), while Jordan came in the fourth place (1 in 14) preceding Turkey (1 in 23). When including the Palestine refugees under UNRWA’s mandate, the figures rise to one in five people for Lebanon and one in three people for Jordan. On the other hand, there was a major offset in the number of Iraqi refugees in the region as they were forced to flee the conflict in the Syrian Arab Republic. Spontaneous and humanitarian returns to the Syrian Arab Republic were observed as around 383,100 Syrians returned to their country between 2017 and 2019, with a further 38,600 returns recorded in 2020. Meanwhile, the number of Palestine refugees under UNRWA’s mandate reached 5.7million in 2020 (UNHCR, 2021b).

- According to Eurostat, Cyprus witnessed a record rise in the number of first-time asylum applications in 2019. At 12,695, it was the highest recipient of asylum applications per capita among the EU member states. The breakdown of the nationalities of new asylum applicants in 2019 was 20 per cent Syrians, 12 per cent Georgians and 11 per cent Indians. In 2020, Cyprus received a total of 7,500 new asylum applications, of which 24 per cent were from Syria, 15 per cent were from India and 9 per cent were from Cameroon (European Commission, 2020).

Internal displacement

- Conflict and violence in 2020 triggered about 143,000 new displacements in Yemen while natural disasters displaced a record 223,000 in Yemen. Governorates data show that many have been displaced for the second time, highlighting vulnerability. Yemen’s crisis is still the world’s most severe as more than 50 per cent of the pre-war population required humanitarian assistance and more than 3.6 million people were internally displaced as of the end of 2020 (ibid).

- Demolition and confiscation of homes triggered 3,000 new displacements among Bedouin and other Arab Israelis in Israel, and a further 1,000 new displacements in the Palestinian Territories, with the West Bank recording its highest number of displacements since 2016. The number of estimated IDPs in the Palestinian Territories stood at 131,000 by the end of 2020 (ibid).

- On the other hand, conflict in Iraq continued to dwindle in 2020 and the number of people living in displacement as of the end of 2020 declined again by 21 per cent from 2019. Similar peaceful resolution to hostilities in Libya allowed around 148,000 displaced persons to return home as well. (ibid).

- Re-eruption of the Armenian-Azerbaijani conflict over Nagorno-Karabakh triggered 84,000 new displacements in Azerbaijan between September and November 2020, bringing the total number of IDPs in the country to 735,000 by the end of 2020. The violent clashes also displaced around 90,000 people from Nagorno-Karabakh during the same period, as well as 800 new displacements in the Syunik and Gegharkunik provinces of Armenia in 2020 (Ibid).

- Cyprus had an estimated 228,000 displaced people by the end of 2020 and this number also includes people displaced since 1974 (ibid).

- There were an estimated 304,000 IDPs in Georgia by the end of 2020 as a result of separatist conflicts in South Ossetia (1991-1992), Abkhazia (1992-1993) and a third wave due to an armed conflict with Russia in 2008 (ibid).

Migrant deaths

IOM’s Missing Migrants Project (MMP) has recorded more than 47,000 fatalities during migration worldwide from 2014 until January 2022. Almost half (over 23,800) of the recorded fatalities occurred in the Mediterranean Sea, deeming it the deadliest region for migration in the world. MMP recorded more than 1,800 fatalities on the Eastern Mediterranean Route between 2014 and 2021, the deadliest years were 2015 and 2016 when more than 1,200 deaths were recorded. Most of the migrants who perished on this route were Syrians, Iraqis and Afghanis fleeing conflict. From 2014 to 2016, migrants who originated from Western Asia comprised the second largest population group who died while crossing the Mediterranean Sea. The Black Sea route from Turkey to Bulgaria and Romania has also witnessed two tragic incidents in 2014 and 2017, leading to 76 total migrant fatalities. MMP also recorded 181 fatalities on land routes between Turkey and Europe and overall more than 1,200 additional fatalities during migration in Western Asia from 2014 until 2021. During 2021, the MMP has also recorded 21 deaths on the Belarus-EU border. The majority were from West Asian countries in conflict or transition (7 Iraqis, 4 Syrians, 2 Palestinians and 2 Yemenis). (IOM, 2022d). Given that most deaths during migration occur on irregular routes, these numbers should be considered a minimum estimate of the true number of lives lost, as it is extremely likely that many migrant deaths in this context go unrecorded.

Main migration routes:

Eastern Mediterranean Route

The Eastern Mediterranean route (EMR) focuses on migratory movements in the EMR region, with Turkey being the key transit country. The EMR has witnessed increased migratory movements including a large number of refugees in 2015, mainly fleeing the Syrian conflict. However, arrivals have sharply decreased following the EU-Turkey Statement in March 2016, which stipulates that all new irregular migrants arriving on the Greek islands will be returned to Turkey if they do not seek asylum or their asylum request is rejected, in addition to a Syrian resettled in the EU for every Syrian returned to Turkey. In 2019, Turkey prevented around 84,000 sea departures and more than 41,000 land departures of migrants to the EU. However, migratory pressure in the second half of 2019 in the Eastern Aegean Sea and towards Cyprus saw the highest total in detected EMR crossings since 2016. Since the share of Afghan nationals crossing the EMR has increased, closely followed by Syrians, Iraqis, Iranians, and some Turkish nationals. Around half of all migrants on this route were rescued in search and rescue operations (Frontex, 2020).

In 2019, while registered new arrivals to Europe decreased by 13 per cent compared to 2018 and 32 per cent compared to 2017, there was a sharp increase in arrivals along EMR via Greece, Bulgaria and Cyprus, coupled with an increase in migrants and refugees transiting through the Western Balkans (IOM, 2020c). The number of arrivals in Cyprus tripled in 2019 (7,821) in comparison to 2017. (IOM, 2021e). However, while the EMR constituted the highest share of total maritime arrivals to Europe throughout all of 2019, it significantly dropped to 21 per cent of maritime arrivals in 2020 to Greece (14,785), Bulgaria (3,399) and Cyprus (2,965). Significant increase in movements in the Western Balkans were still observed throughout 2020 (IOM, 2021f). Arrivals to Greece saw a declining trend in arrivals during 2021 (9,026) while arrivals to Cyprus on the contrary sharply increased again during the first ten months of 2021 (8,870) in comparison to the entire year of 2020. Arrivals to Bulgaria during 2021 (10,799) have also starkly surpassed the arrivals during 2020 (IOM, 2021g).

Greece-Turkey Border

The land border between Turkey and Greece, partially demarcated by the Evros river, also constitutes a strategic entry point into the EU. However, migrants face many hazards crossing the river and there is limited data on migration flows due to difficulties in border monitoring. The province of Edirne remains a popular transit point for migrants who attempt to cross from Turkey to Greece and to smaller extent Bulgaria. The Turkish Armed Forces intercepted 5,227 migrants attempting to cross the land border during 2020 (IOM, 2021h). In the third quarter of 2021, 58 per cent of migrants crossed into Greece through the land border (Evros region) with Turkey, while the remaining crossed the Aegean Sea and reportedly landed on several Greek islands, of which around half landed on Samos and Lesbos. Nevertheless, overall land and sea arrivals to Greece have decreased by 20 per cent in the third quarter of 2021 in comparison to the same period in 2020 and sharply fell by 93 per cent in comparison to the same period in 2019, mainly due to the low sea arrivals on EMR in 2021 (IOM, 2021i). Recorded land arrivals constituted 52 per cent of the total arrivals to Greece during 2021, whereas sea arrivals were highest during the fourth quarter (1,824) (IOM, 2022e).

Eastern Corridor (Horn of Africa-Arabian Peninsula)

Travelers on this route mostly come from the Horn of Africa and exhibit stepwise migration, traveling on land from Ethiopia to the coast of Somalia or Djibouti, then crossing the sea to Yemen before crossing the land border with Saudi Arabia. Despite the conflict in Yemen, following years continued to witness a large number of arrivals. Others also reached North Africa through the coasts of Yemen to cross the Mediterranean Sea to Europe. As of April 2017, an estimated total of 95,807 persons had also fled Yemen inversely to Somalia and Djibouti (RMMS, 2017). In 2020, 37,535 arrivals were recorded in Yemen, whereby flows were predominantly male (72%) and largely dominated by Ethiopians (92.2%). 94 per cent of the migrants intended Saudi Arabia as their destination due to high salary expectations and the success stories of returnees. Migration along the Eastern route is also fueled by unemployment, insufficient wages and agrarian challenges. However, the inability to move towards Saudi Arabia also meant that many have attempted to return to the Horn of Africa again using the same smuggling networks. 6,787 migrants have returned from Yemen since March 2020. Additionally, 50,527 Ethiopian and Yemeni migrants were returned from Saudi Arabia (IOM, 2021j). Around 130,00 movements were recorded between January and June 2021, increasing in particular by over 600 percent during the second quarter of 2021 in comparison to the same period in 2020, which was highly impacted by COVID-19 mobility restrictions. The intended destination for most migrants was Saudi Arabia (56%) while 40 per cent intended Yemen, although almost always as transit and not as a final destination (IOM, 2021d). During 2021, 27,693 migrants from the Horn of Africa arrived on the shores of Yemen. On the other hand, between May 2020 and December 2021, IOM tracked 16,641 spontaneous returns from Yemen of Ethiopian migrants, 10,547 of which were in 2021. During the same period, Since May 2020, 20,217 migrants have made this perilous return journey back to Djibouti (16,641) and to Somalia (3,576) including 13,125 returns in 2021 (IOM, 2022e).

Back to topData sources

United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs (UN DESA) - the Population Division regularly publishes data on the international migrant stocks by country. Estimates draw on official national statistics on the foreign population residing in each country.

United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Western Asia (UN ESCWA) - The commission often publishes reports on migration and development in ESCWA member countries, particularly in the Arab Mashreq and GCC member countries.

Eurostat – The database supplied by members of the European Statistical System disseminates more than 250 tables of European statistics relevant to migration These are often disaggregated by sex, age, country of birth and country of citizenship. The Asylum and Managed Migration section provides statistics on asylum, implementation of the Dublin regulation, residency permits, migrant children and the enforcement of immigration legislation.

International Labour Organization (ILOSTAT) – ILO publishes global estimates on migrant workers, labour force surveys, and statistical information on migrant worker stocks, inflows and outflows. Some of the sources include household surveys, official visas and border data, and reports by social security and recruitment agencies.

Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre (IDMC) - provides data estimates on internal displacement across the world. Country profiles offer data on IDP stock and flow numbers, disaggregated by drivers of displacement. The profiles also provide an overview of conflict and disaster events that triggered migration. The profiles of Western Asian countries and places can be found here: Armenia, Azerbaijan, Cyprus, Georgia, Iraq, Israel, Jordan, Lebanon, Oman, Saudi Arabia, Syria, Turkey, Yemen and the Palestinian Territories.

Displacement Tracking Matrix (DTM) – provides data on the mobility, vulnerabilities, and needs of displaced and mobile populations through assessments, mobility tracking and monitoring of migration flows. For Western Asia, DTM is active in Armenia, Cyprus, Iraq, Lebanon, Turkey and Yemen.

OCHA’s Humanitarian Data Exchange (HDX) – an open data consolidation platform providing data and thematic information on a variety of humanitarian topics, submitted by humanitarian organizations and other users. Data on Western Asia can be accessed through an interactive map.

Migration Policy Institute (MPI) – provides research and analysis by prominent scholars on complex policy questions on issues regarding the migration-development nexus. Research is divided by regions and many publications can be found on migration in Middle Eastern and European countries.

Gulf Labour Markets, Migration, and Population (GLMM) Programme – A major think-tank that provides data, analyses, and recommendations on the management of Gulf labour migration and labour markets. GLMM is a joint programme of the Gulf Research Center (GRC) and the Migration Policy Centre (MPC) of the European University Institute (EUI).

Back to topData strengths and limitations

Like the rest of the world, data on migration flows are very limited in the region due to the focus on inflows more than outflows. Conflicts in the region also constrain access for tracking movements. Western Asia is also not available as a regional classification in related literature (IOM, 2020d).

Migration research in the Gulf states is as recent as the 2000s introduced a new avenue of empirically grounded sociological/anthropological work. However, censuses in the GCC states are not routinely conducted. Data on status-related flows are very rare in Gulf statistical records, while data on irregular migration in the region is scarce as little to no information exists on the births and deaths of persons in an irregular situation. Information is usually deduced from the numbers of amnesties, apprehensions and deportations and sometimes, infiltration. Migrant stocks are also not disaggregated by nationality in the GCC records (De Bel-Air, 2017).

Back to topRegional stakeholders and processes

League of Arab States (LAS) - Member states include the twelve Arab countries in Western Asia. LAS has focused on the improvement of migration policies through enhanced dialogues and mainstreaming migration within declarations, including the Tunis Declaration in 2004, Brasilia Declaration in 2005, Khartoum Declaration in 2006, Doha Declaration in 2009, Arab Economic and Social Development Summit in 2009, and the Africa-Arab Summit in 2013 (IOM, 2015).

- • Arab Regional Consultative Process on Migration and Refugees Affairs (ARCP) – An Arab Platform created in 2015 by the LAS Secretariat bringing together Member States to tackle various migration questions, understand effects and trends, and help governments to participate in a unified vision of global migration-events. The LAS is the permanent Chair and Secretariat of the ARCP (IOM, 2019).

- • Arab Labour Organization (ALO) - One of the specialized organizations within the Arab League, concerned with labour and workers affairs at the national level. The Arab Charter for Labor was adopted in 1965 and in 1970, the Fifth Conference of Arab Labor Ministers declared the establishment of the ALO. The organization is invested in the contemporary issues of labour migration, both regular and irregular.

The Abu Dhabi Dialogue (ADD) - An interregional dialogue among 18 governments in Asia and GCC countries. It was initiated by the UAE (in 2008), which is the current ADD Chair and host of the ADD Secretariat. The ADD holds annual meetings with senior officials as well as ministerial meetings. ADD’s third ministerial meeting witnessed the adoption of the Kuwait Declaration to address decent work for migrant workers, while the fifth ministerial meeting adopted the Dubai Declaration on the use of IT, standards and accreditations.

Syria Crisis Regional Refugee & Resilience Plan (3RP) - A coordination, planning, advocacy, fundraising, and programming platform founded in 2015 for humanitarian and development partners to respond to the Syria crisis. It comprises one regional plan and five country coordination mechanisms: Turkey, Lebanon, Jordan, Iraq, and Egypt.

The Prague Process (PP) – A migration dialogue promoting cooperation in migration management among the countries of the European Union, Schengen Area, Eastern Partnership, Western Balkans, Central Asia, Russia and Turkey. PP was launched in the 1st Prague Process Ministerial Conference in 2009. The 2nd Ministerial Conference in 2011 saw the adoption of the Prague Process Action Plan 2012-2016, which aimed towards combatting irregular migration; readmission, voluntary return and reintegration; regular migration pathways; integration; mobility and development; and asylum and international protection.

Further reading

International Organization for Migration

2021 Iraq — Displacement Report 124 (October - December 2021). Displacement Tracking Matrix, IOM Iraq.

2022 Yemen — Rapid Displacement Tracking Update (06 February - 12 February 2022) . Displacement Tracking Matrix, IOM Yemen.

2021 Yemen — Flow Monitoring Points | Migrant Arrivals and Yemeni Returns From Saudi Arabia in October 2021). Displacement Tracking Matrix, IOM Yemen.

2021 Europe — Mixed Migration Flows to Europe, Quarterly Overview (July - September 2021).. Displacement Tracking Matrix, IOM.

2021 Turkey — Quarterly Migrant Presence Monitoring (July-September 2021). Displacement Tracking Matrix, IOM.

United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Western Asia and International Organization for Migration

2020 Situation Report on International Migration 2019: The Global Compact for Safe, Orderly and Regular Migration in the Context of the Arab Region Executive Summary. ESCWA & IOM.

International Organization for Migration, Arab Labor Organization and Partners in Development

2010 Intra-Regional Labour Mobility in the Arab World. IOM & ALO & PiD.

Chindea, A. et al

2008 Migration in Azerbaijan: A Country Profile 2008. Eds. Sheila Siar. IOM.

Chindea, A. et al

2008 Migration in Georgia: A Country Profile 2008. Eds. Sheila Siar. IOM.

Devillard, A.

2012 Labour Migration in Armenia: Existing trends and policy options. IOM.

Shah, N.

2004 Arab Migration Patterns in the Gulf, in Arab Migration in a Globalized World. IOM & The Arab League, pp. 91-115.

Shah, N. et al

2017 Skillful Survivals – Irregular Migration to the Gulf. Eds. Philippe Fargues & Nasra Shah. Gulf Research Centre.

Thoillet, H.

2016 Managing migrant labour in the Gulf: Transnational dynamics of migration politics since the 1930s. International Migration Institute.

Kapiszewski, A.

2004 Arab Labour Migration to the GCC States, in Arab Migration in a Globalized World. IOM & The Arab League, pp. 115-134.

Khouri, R.

2004 Arab Migration Patterns: The Mashreq, in Arab Migration in a Globalized World. IOM & The Arab League, pp. 21-34.

Fargues,P. and De Bel-Air, F.

2015 Migration to the Gulf States: The Political Economy of Exceptionalism, in Acosta Arcarazo D. & and Wiesbrock A., Global Migration: Old Assumptions, New Dynamics, Praeger, pp. 139-166.

International Crisis Group

2008 Failed Responsibilities: Iraqi Refugees in Syria, Jordan, and Lebanon, Middle East Report No. 77.

1 As defined by the UN Statistics Division: Armenia, Azerbaijan, Bahrain, Cyprus, Georgia, Iraq, Israel, Jordan, Kuwait, Lebanon, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, Syria, Turkey, United Arab Emirates, Yemen and the Palestinian Territories.

2 An economic union consisting of Persian Gulf Arab states (excluding Iraq): Bahrain, Kuwait, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates.

3 This figure includes Palestine refugees under UNRWA’s mandate.

Back to top