Gender and migration

Gender has a big impact on the migration experiences of persons of all genders.

Gender inequalities contribute to heightened risks of human rights violations, and reduced socio-economic outcomes, especially affecting women, girls and gender-diverse persons. Thus, addressing gender dynamics and inequalities within policymaking and planning can contribute to social and economic empowerment and promote gender equality. Overlooking such considerations can expose persons of different genders to further risks and vulnerabilities and perpetuate or exacerbate inequalities.

Johanna is the leader of the Honduran diaspora in Miami. In her role, she promotes fundraising activities to invest in vulnerable communities in her home country. Photo: IOM 2023 / Ismael Cruceta.

The Global Compact for Migration and the New York Declaration for Refugees and Migrants call for more migration data to be disaggregated by sex and age. Greater collection and use of sex-disaggregated data supports stronger policy making, resource allocation and action to understand and address gaps and inequalities in capacities and vulnerabilities along the migration continuum. However, disaggregating data by gender is important to provide a full picture of gender dynamics in migration, their impact on persons of all genders and to address gender discrimination.

Key trends

This section predominantly uses migration data disaggregated by sex, which contributes to the understanding of sex and gender-based dynamics of human mobility. Though this is important, disaggregating data by gender is important to understand the diverse socioeconomic realities of individuals of different genders (Hennebry et al., 2021). In this section, the terms “women”, “girls”, “females”, “men”, “boys” and “males” refer to sex-disaggregated data on adult females, female children, females of all ages, adult males, male children, and males of all ages respectively. These terms are used to facilitate ease of reading and do not refer to data disaggregated by gender unless otherwise specified.

The share of female migrants has not changed significantly in the past 60 years. However, more female migrants are migrating independently for work, education and as heads of households. Despite these improvements, female migrants may still face greater discrimination, are more vulnerable to mistreatment, and can experience double discrimination as both migrants and as females in their host country in comparison to male migrants. Nonetheless, male migrants are also exposed to vulnerabilities in the migration processes. Therefore, the collection and use of gender-responsive migration data have the potential to promote greater equality and offer opportunities for disadvantaged gender groups.

Female migrants

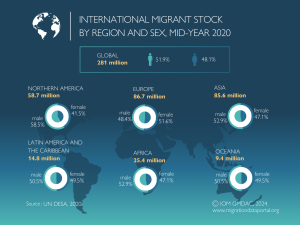

At mid-year 2020, female migrants comprised somewhat less than half, 135 million or 48.1 per cent, of the global international migrant stock (UN DESA, 2020). The share of female migrants has declined from 49.4 per cent at mid-year 2000 to 48.1 per cent at mid-year 2020, whereas the proportion of male migrants grew from 50.6 per cent at mid-year 2000 to 51.9 per cent at mid-year 2020 (ibid.).

Regional trends:

Asia and Africa

From mid-year 2000 to 2020, the estimated stock of male international migrants grew significantly by 89 per cent in Asia, to 49.8 million, whereas the share of female international migrants in Asia grew by only 57 per cent (UN DESA, 2020). This growth in male migrants has been fuelled by the increasing demand for male migrant workers in the oil-producing countries of Western Asia. The share of female migrants at mid-year 2020 was lower both in Asia (41.8%) and in Africa (47.1%) (UN DESA, 2020). Thus, male international migrants significantly outnumber female international migrants in these regions. However, between mid-year 2000 and 2020, the increase in the estimated stock of female international migrants in Africa (69 per cent) was slightly higher than the increase in male migrants (68 per cent) (UN DESA, 2020).

Europe and Northern America

At mid-year 2020, female migrants comprised slightly more than half of all international migrants in Europe and Northern America. The share of females among all international migrants reached 51.6 per cent in Europe and 51.8 per cent in Northern America (UN DESA, 2020). The larger share of female migrants in these regions is because of a combination of two factors: the presence of older migrants in the population and the tendency of longer life expectancies of female migrants in comparison with males.

Latin America and the Caribbean

At mid-year 2020, female international migrants (49.5%) were slightly outnumbered by the proportion of male international migrants (50.5%) in Latin America and the Caribbean. Moreover, during mid-year 2000-2020, the stock of male international migrants grew slightly faster than that of female international migrants (UN DESA, 2020).

Oceania

At 50.5 per cent, female migrants accounted for a slightly higher share than male migrants in the international migrant stock in Oceania at mid-year 2020 (UN DESA, 2020). In the two decades between mid-year 2000 and mid-year 2020, the estimated number of female migrants increased slightly faster than male international migrants in Oceania (ibid.).

Female migrant workers

The slightly larger presence of males in the international migrant stock was also reflected in the proportion of male migrant workers. In 2019, there were more male migrant workers, 99 million or 58.5 per cent, than female, 70 million or 41.5 per cent (ILO, 2021). Among international migrants globally in 2019, females represented a lower share (47.9%) and women had a relatively lower labour market participation rate compared to men (59.8% vs. 77.5%) (ibid.).

Selmy Jimenez, 46, arrived in Ecuador in 2018. In Venezuela, due to the economic crisis, she started making and selling ecological bags to replace those used in supermarkets. When she left her country, the city of Guayaquil, Ecuador, welcomed her and here she has been able to restart her business with the support of training programmes led by IOM. Photo: IOM 2023 / Ramiro Aguilar Villamarín

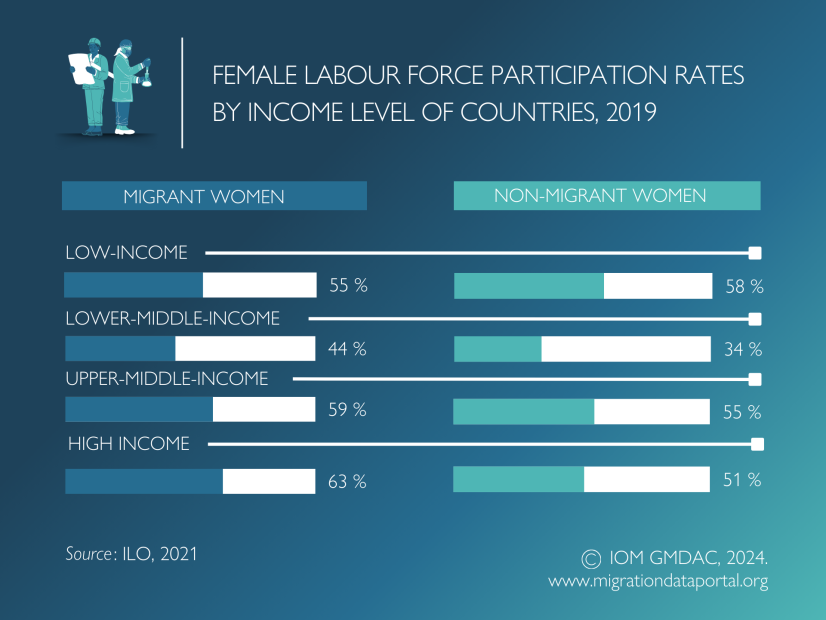

Significant regional variations existed in the share of women among total migrant workers. In 2019, women represented more than 50 per cent of all migrant workers in Northern, Southern and Western Europe but the share was below 20 per cent in the Arab States (ILO, 2021). Though the labour force participation of migrant women was lower than that of migrant men, the labour force participation rate of migrant women was higher than that of non-migrant women in many countries.

High-income countries had the highest participation gap with 12 percentage points between migrant women and non-migrant women, followed by lower-middle income countries (with a participation gap of 10 percentage points) (ibid.). The lower labour force participation of migrant women in low-income countries may be attributed to the prevalence of informal employment, which is not fully captured in ILO estimates within these nations (Guallar Ariño, E., 2023).

Migrant women in the OECD

Six OECD countries received a higher number of migrant women than men in 2021. Notably, the United States, Australia, Ireland, and Israel had the highest shares of women in migrant inflows, with their shares remaining relatively consistent, reflecting the prevalence of family migration. Conversely, this share is approximately 40 per cent of in Germany, Austria, and most Central and Eastern European countries (OECD, 2023.

Between 2021 and 2022, there were significant differences in the employment rates of migrants by gender. In non-European OECD countries, the increase in the employment rate of migrant women was higher than that of men, while the opposite trend was observed in OECD-Europe, despite some progress in labour market inclusion for migrant women. According to OECD estimates, narrowing the immigrant gender gap in employment to align with that of native-born individuals could lead to an additional 5.8 million immigrant women gaining employment in OECD countries (ibid).

Immigrant mothers had an employment rate 20 percentage points lower than their native-born peers in the OECDin 2021 This gap has to be also addressed since evidence from European Union countries shows that the employment of migrant mothers seems to have a positive impact on the labour market outcomes of their children (ibid).

Female diasporas and remittances

International migration stock estimates often serve as a proxy for assessing diaspora communities due to the absence of a standardized definition and limited data availability on diasporas (Schöfberger, I. and Manke, M., 2023).

Migrants and diasporas may contribute to their countries of origin or descent and destination, as well as to transnational societies, in different ways. Contributions may refer to transfers of human, social, cultural, and economic capital. However, estimates of these transfers globally are still inconsistent, and some have not yet been sufficiently quantified, such as the contributions of human capital (ibid).

In terms of economic contributions, personal remittances remain the most recognized and quantifiable form (ibid). However, the World Bank’s estimates on global remittances, which are the main data source on remittance data, lack disaggregated data by sex, resulting in limited evidence on comparative data of remittances sent by female migrantsand male migrants (Guallar Ariño, E., 2023). Nevertheless, evidence suggests that women remit the same or even greater amounts than men, despite often earning less and paying more in transfer fees (UN Women, 2020).

Gender-responsive migration policies

According to an assessment on 84 countries conducted by the Migration Governance Indicators (MGI), less than one in four countries (23%) incorporate a gender perspective into their national migration strategy (IOM, 2024). When the needs of migrants based on their sex and gender are disregarded, it prevents them from having equal access to opportunities and to fully contribute to their host countries.

Another assessment by UN DESA, IOM and OECD (2021) found that only 69 per cent of 111 countries have formal mechanisms to ensure that migration policies are gender responsive (UN DESA, IOM and OECD. 2021). The assessment was conducted to measure the progress of SDG indicator 10.7.2 and the number of countries with migration policies to facilitate orderly, safe, regular and responsible migration and mobility of people.

Displaced women and girls

Across borders

At the end of 2022, women and girls accounted for an estimated 51 per cent of all refugees globally (UNHCR, 2023). The five top countries of origin of female refugees were the Syrian Arab Republic (2.9 million), Ukraine (2.7 million), Afghanistan (2.6 million), South Sudan (1.2 million) and Myanmar (587,000) (UNHCR, 2024).

"When we were travelling on the train from Kyiv to Uzhhorod, I looked at my old train ticket and realized I was once again leaving to start my life from scratch.” Photo of Tatiana holding her ticket, by IOM 2023 / Jorge Galindo

The ongoing war in Ukraine has led to the largest refugee surge to the OECD area since World War II. As of June 2023, there were around 4.7 million displaced Ukrainians in OECD countries, among which around 70 per cent of adult refugees were women and 30 per cent of all refugees were children (OECD, 2023).

Internally displaced women and girls

At the end of 2022, 35.8 million women and girls were living in internal displacement due to conflict, violence and disasters, and they accounted for slightly more than 50 per cent of all IDPs (IDMC, 2023). Among the 35.8 million internally displaced women and girls (IDPs), female IDPs between 25 and 56 years had the highest share (40.6% or 14.5 million) (ibid).

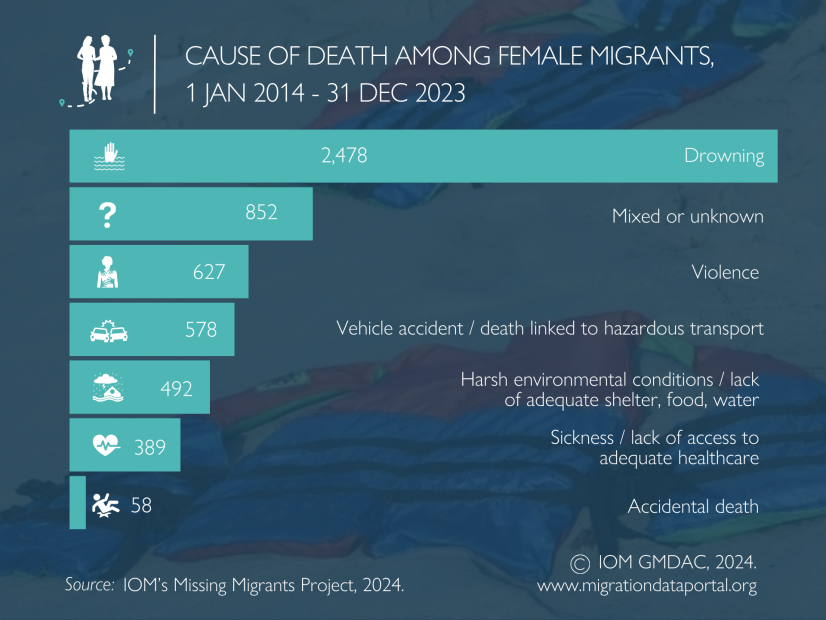

Missing female migrants

Information on sex is only available for 1 out of 3 people (22,618 of the nearly 63,307 people) who lost their lives during migration globally between January 2014 and December 2023 (IOM’s Missing Migrants Project, 2024). Of these 22,618 migrant deaths where data on sex are available, 24.2 per cent were women. Nearly half of the deaths of identified female migrants occurred during sea crossings, where the survival chances of women were limited as they were pregnant or caring for their children on board.

Definition

Key terms and concepts that pertain to gender and migration are as follows:

Sex-disaggregated data refer to the “differentiation of information by sex categories as typically listed on official identification, including male, female and other designations such as O, T or X, depending on the country.” (Hennebry et al., 2021).

Sex refers to “The classification of a person as having female, male and/or intersex sex characteristics. While infants are usually assigned the sex of male or female at birth based on the appearance of their external anatomy alone, a person’s sex is a combination of a range of bodily sex characteristics” (IOM, 2021).

Gender-disaggregated data refer to “information about an individual’s gender identity. Gathering accurate gender-disaggregated data requires respondents to self-identify their gender, which may or may not correspond with their sex assigned at birth or the gender attributed to them by society” (Hennebry et al., 2021).

Gender refers to “The socially constructed roles, behaviours, activities and attributes that a given society considers appropriate for individuals based on the sex they were assigned at birth“ (IOM, 2021).

There are several relevant concepts such as gender equality and gender-based violence (GBV) that are widely discussed in the migration field:

Gender equality refers to “The equal rights, responsibilities and opportunities of all individuals of all genders. Equality does not mean that all individuals are the same, but that rights, responsibilities and opportunities will not depend on one’s sex assigned at birth, physical sex characteristics, gender norms assigned by society, gender identity or gender expression. Gender equality also requires that the interests, needs and priorities of all individuals should be taken into consideration. Equality between people of all genders, including cisgender and transgender men and women, other transgender people, non-binary people, and people with other diverse gender identities, is seen both as a human rights issue and a precondition for, and indicator of, sustainable people-centred development” (IOM, 2024).

Gender-based violence, according to the The Inter-Agency Standing Committee (IASC), is defined as “any harmful act that is perpetrated against a person’s will and that is based on socially ascribed (i.e. gender) differences between males and females. It includes acts that inflict physical, sexual or mental harm or suffering, threats of such acts, coercion, and other deprivations of liberty” (IOM, 2019).

IOM recognizes that each person has a gender identity, which refers to their "deeply felt internal and individual experience of gender, which may or may not correspond with the sex they were assigned at birth, or the gender attributed to them by society. It includes the personal sense of the body which may involve a desire for modification of appearance or function of the body by medical, surgical or other means” (IOM, 2021).

Back to topData sources

Data on gender and migration are collected and analyzed separately for male and female migrants. Although sex-disaggregated data are not always collected, major data sources that collect sex-disaggregated migration-related data are population censuses, administrative registers, and sample surveys such as labor force surveys and income and living condition surveys. Data from these data sources are compiled in databases. The following are the databases on migration disaggregated by sex.

Global

The Population Division of the United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs (UN DESA) provides several international migrant stock datasets for all countries and areas and disaggregates data by sex, age and origin. UN DESA publishes datasets on a bi-yearly basis. Its latest dataset on the international migrant stock was published in 2020.

The International Labour Organization’s (ILO) Department of Statistics (ILOSTAT) has a database on Key Indicators of the Labour Market (KILM). This database provides datasets on labour migration that are grouped into three major themes: international migrant stock, nationals abroad and international migrant flow. These themes contain estimates of demographic stocks/flows and labour migrant stocks/flows and are predominantly disaggregated by sex and age. The database provides labour migration statistics for all countries and areas of the world on an annual basis.

The ILO reports "Global Estimates on Migrant Workers" from 2015, 2018 and 2021 provide estimates on the share of labour migrant workers among the total international migrants and highlights regions and industries where international migrant workers are established. They also present demographic characteristics of international labour migration, and the 2015 report specifically focuses on the proportion of female and male migrant workers in domestic work globally.

IOM’s Migration Law Database consolidates information on international migration law and frames it in a comprehensive manner. It draws together migration-related instruments including gender-related norms in the migration context. The database contains relevant international, regional and bilateral treaties, international and regional resolutions, declarations and other instruments.

IOM and Polaris pulled together existing data on human trafficking and created the Counter-Trafficking Data Collaborative (CTDC) repository. It contains data on cases of human trafficking disaggregated by sex and age. An anonymized version of this dataset is available for public download. In 2022, CTDC published a dataset on victims and their accounts of perpetrators for which IOM and Microsoft Research developed and refined an algorithm to generate synthetic data from IOM's sensitive victim case records.

BRIDGE was a gender and development research service at the Institute of Development Studies, which advocated for the significance of a gender perspective in endeavours to reduce poverty and promote social justice in the migration processes. Among other development-related objectives, BRIDGE focused on gender aspects of migration.

The Gender Dimensions of Forced Displacement (GDFD) Research Program was established by the World Bank in partnership with the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). The program looked at a variety of interrelated drivers and manifestations of gender inequality, such as income and multidimensional poverty, livelihoods, gender norms, and gender-based violence including the risks of experiencing intimate partner violence and child marriage.

Asia

The ILO Regional Office for Asia and the Pacific has a database called the International Labour Migration Statistics (ILMS) Database which compiles a variety of statistical sources on international migrants and international migrant workers. It generates statistical data from population and housing censuses, labour force surveys, household surveys, enterprise surveys and administrative records. The ILMS Database presents datasets on the international migrant stock, international migrant flow and nationals abroad. Data are broken down by sex, age, employment status, education, occupation, economic activity and origin.

Europe

The Gender Statistics Database, a database of the European Union (EU)’s European Institute for Gender Equality (EIGE), provides statistical evidence on numerous themes including migration from all over the EU and beyond, at the EU, Member State and European Level. It contains estimates on the immigrant stock, immigration and emigration flows, and migration and education. Data are disaggregated by sex, age, migration status and 55 other migration-related indicators. This database is used by the Member States to comply with the European Commission’s (EC) Strategy on Gender Equality and monitor their progress.

Data on population demography and migration are collected by Eurostat on a yearly basis. The Population (Demography, Migration, and Projections) database has a dataset on migration and citizenship data, which is divided into three major thematic groups: immigration, emigration, and acquisition and loss of citizenship. The estimates are mostly disaggregated by sex, age group, citizenship, country of birth, and ranking in the Human Development Index.

Eurostat’s database on asylum and managed migration is based on data collected from the Member States’ Ministries of Interior and related Immigration Agencies. The database presents data on asylum, residence permits and the enforcement of immigration legislation (EIL). Data on asylum and residence permits are mostly disaggregated by sex and age group.

OECD’s Migration Statistics contains databases on Immigrants in OECD countries (DIOC) and non-OECD countries (DIOC-E). These databases present data on several demographic and labour market characteristics of the population of 32 OECD member countries and 68 non-members. The thematic datasets of this database are broken down by seven core variables: gender (male/female), age, duration of stay, labour market outcomes, field of study, the place of birth and educational attainment.

OECD’s Gender, Institutions and Development database (GID-DB) presents comparative data on gender-based discrimination in social institutions such as legal, cultural and traditional practices and covers 179 countries for 2023. The database consists of variables such as the legal age of marriage, early marriage rates, parental authority in marriage and after divorce, violence against women, reproductive integrity, female genital mutilation, and other gender topics. This database provides datasets on the Social Institutions and Gender Index (SIGI), which measures the extent to which social institutions are discriminatory, to reveal main drivers of gender inequality and their impact on women’s empowerment opportunities. This dataset has 21 variables of discriminatory social institutions that are grouped into five sub-indices such as discriminatory family code, restricted physical integrity, son bias, restricted civil liberties and restricted resources/assets.

By disaggregating and analyzing data by the variables “female” and “male” migrant, researchers produce broad migration statistics on these two different groups. However, to understand more thoroughly the gender patterns present throughout the migration processes, more qualitative studies and inclusion of specific relevant questions in surveys are needed to reveal the power imbalances in migration decisions, labor markets, remittance sending/utilization, and the impact of migration on social relations in the households and communities experiencing out-migration.

Back to topData strengths & limitations

Sex-disaggregated migration data are an essential starting point to understanding and addressing the difference in experiences, opportunities and outcomes of migrants of different genders, as well as questioning erroneous gender stereotypes such as labelling women as always vulnerable and men as never vulnerable.

By using sex-disaggregated data sources, policymakers will be able to initiate effective evidence-based programmes,.

Nevertheless, there are some limitations to existing data and data sources:

Sex-disaggregated and gender-disaggregated data are not always collected or estimated. For example, World Bank – KNOMAD’s estimates on remittances are one of the datasets providing evidence on the most direct and well-known link between migration and development. However, these data are not disaggregated by sex or gender. This makes it difficult to distinguish gender differences in remittance sending such as the amount of money, frequency, channels and reasons.

Disaggregated data are particularly complex to collect in certain contexts, such as displacement situations. The Global Internal Displacement Database (GIDD) provides a limited amount of sex-disaggregated data on internal displacement since data are not collected by sex; data are instead collected by household. The IDMC’s Internal Displacement Index discovered that in 2022, 26 countries did not publish sex-disaggregated data for conflict and displacement (IDMC, 2023).

Similarly, data on migrants’ deaths are only occasionally disaggregated by sex because it is highly contingent on the identification of bodies (IOM, 2019). There are other reasons why data are rarely disaggregated by sex. Some authorities have low statistical capacities to produce more granular data; are unwilling to collect and disaggregate data; and/or aim to protect migrants’ postmortem privacy and therefore disseminate aggregated data.

Sex-disaggregated data alone may not provide a comprehensive understanding of migration experiences across all genders since a person's sex may not align with their gender identity or expression. Disaggregating data not just by sex but also by gender can lead to a more nuanced comprehension of the dynamics of human mobility and the varied experiences of migrants and displaced individuals, and eventually to more informed programming and policymaking.

Most data producers, however, do not include gender mainstreaming methodologies in their data collection to capture people who identify as something other than male or female. Despite attempts to disaggregate migration data by sexual orientation and gender identity, data are hardly ever disaggregated by LGBTIQ+ identification. Moreover, the definition of gender, which is often viewed as being the same thing as sex or equated to only female migrants, should be more comprehensive to include the different needs of men and persons identifying as LGBTIQ+.

While there is a need to increase the availability of gender-disaggregated data, there are also ethical considerations and potential risks associated with standardized approaches to collecting data on individuals' gender identity, expression, sexual orientation, and sex characteristics. This concern is particularly pronounced in countries with discriminatory laws, policies and cultural norms, where data collection can put vulnerable groups at risk and data collection outcomes might be unreliable.

Further reading

| Abel, Guy J. | |

|---|---|

| 2022 |

Gender and Migration Data. KNOMAD / WORLDBANK, 2023. |