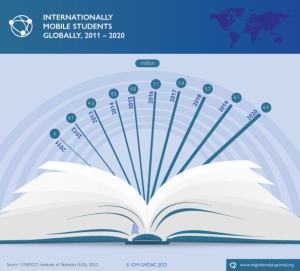

International students

The numbers of internationally mobile students are increasing and destinations diversifying. “Internationally mobile students” typically are issued a student visa or permit to pursue a tertiary (or higher) degree in the destination country. These individuals are also called “degree-mobile students”, to emphasize the fact that they would be granted a foreign degree, and to distinguish them from “credit-mobile students” on short exchange or study-abroad trips.

Definition

Definition

“Internationally mobile students are individuals who have physically crossed an international border between two countries with the objective to participate in educational activities in the country of destination, where the country of destination of a given student is different from their country of origin” (UNESCO Institute of Statistics, n.d.).

There are many overlapping definitions of “international students.” Since 2015, UIS (UNESCO Institute of Statistics), OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development) and EUROSTAT (the European Union’s statistical office), have agreed upon the above definition of “internationally mobile students.”

This definition captures the most important group of international students: those who moved to a foreign country for educational purposes (UNESCO, n.d.). This definition also focuses on students who are enrolled for a tertiary (or higher) degree; therefore the length of stay is typically more than one year, and up to 7 years.

Internationally mobile students are different from two other common definitions of international students, namely “foreign students” and “credit-mobile students.”

- Foreign students - refers to non-citizens who are currently enrolled in higher education degree courses. This definition does not distinguish between students holding non-resident visas and those with permanent resident status. The former usually arrive and stay independently, while the latter usually migrate because their parents moved, making them 1.5-generation immigrants.

- Credit-mobile students - refers to “study-abroad” or exchange students, such as those in the EU’s Erasmus programme. These students remain enrolled in their home countries while receiving a small number of credits from foreign institutions (Van Mol and Ekamper, 2016). Due to their fluid enrolment status, most statistics on international students do not include credit-mobile students.

While the agreed-upon definition of internationally mobile students has been used since 2015, data on international students reflect the long-standing differences between the three definitions.

Key Trends

In 2021, there were over 6.4 million international students globally, up from 2 million in 2000 (UIS, 2023). Available data show that 5 out of 7 international students were enrolled in educational programmes in high-income countries. Slightly more than half of the 6.4 million international students were in ten countries: The United States of America, the United Kingdom, Australia, Germany, Canada, France, Türkiye, China, the Netherlands and the Republic of Korea (data on international students in the Russian Federation – which hosted the fourth highest number of international students globally in 2019 – are not available for following years)(ibid.). More than 60 per cent of international students were from middle-income countries of origin. Prominent countries of origin of international students in 2021 included China (16% of all international students globally), India (8%), Viet Nam (2%), Germany (2%), Uzbekistan (2%), France (2%) and the United States of America (GMDAC analysis based on UIS, 2023).

More than 1.9 million international tertiary-level students (counted as first residence permits issued to students) newly moved to OECD countries in 2022 (OECD, 2023a). In 2021, a total of over 4.3 million international students were enrolled in educational institutions in OECD countries (ibid.). The major OECD destination countries in 2021 for international students were the United States of America (hosting 19% of all international students in the OECD countries), the United Kingdom (14%), Australia (9%) and Germany (9%) (ibid.). Among all international students in the OECD countries in 2021, 57 per cent were from Asia (OECD, 2023b). China and India were the main countries of origin, and they accounted for 21 per cent and 10 per cent respectively of all international students in OECD countries in 2021 (OECD, 2023a).

Studies of internationally mobile students tend to focus on the conditions (push and pull factors) that motivate students to study overseas; but policymakers are also interested in international students because they can become highly skilled immigrants in the future.

Data sources

UNESCO’s Institute for Statistics (UIS) provides the most comprehensive data to date on on international students by country of destination and origin (called “inbound” and “outbound” respectively) for more than 100 countries. Countries, by responding to an annual UIS questionnaire, report the number of internationally mobile students they are hosting and information on the students’ countries of origin. Annual data for several countries are available from 1998 to 2021.

OECD provides the total number of international students from various countries of origin who are enrolled in OECD countries of destination. An older indicator in OECD's archived database has data from 1998 to 2012. Between 2003 and 2012, the reported number were further disaggregated into “non-citizen” students and “non-resident” students. The latter category aligns more closely with UIS’s definition of internationally mobile students. A newer indicator provides data on the enrolment of international students from 2013 to 2021 in OECD countries and four non-OECD countries of destination. Both of these indicators are further disaggregated by sex and level of education.

Project Atlas - While UIS and the OECD rely on reports from destination countries, Project Atlas partners with 26 country-specific data providers to obtain data on inbound and outbound flows of international students. With the annual coverage depending on the country, data availability is generally from 2013 to 2012. It is important to note that the number reported by Project Atlas includes exchange and study-abroad students, and as such, the number is likely higher than those reported by UIS or OECD.

Prominent destination countries that host a large share of international students, such as the United States, are increasingly better at maintaining data on international students. These data could provide further breakdowns of international students by sex or age. Such data might be requested from relevant statistical agencies. The United States, for instance, maintains the Student and Exchange Visitor Program (SEVP) database which contains detailed records of international student visas from 2001 to present.

Many studies of international students rely on surveys of potential students to understand their motivations for studying overseas (e.g., Mazzarol and Soutar, 2002), and surveys of current international students to examine their intentions to stay or to leave after graduation (e.g. Han et al., 2015). These surveys typically lack a sampling frame, and therefore could not be treated as representative samples.

Back to topData strengths & limitations

| Pros | Cons | |

|---|---|---|

| UIS data |

Includes many origin and destination countries |

Some numbers are indirect estimates |

| OECD data |

Includes many origin countries |

Includes only OECD destination countries Data prior to 2003 count all non-citizen students. This category is broader than internationally mobile students |

| Project Atlas |

Includes both inbound and outbound student flow estimates |

Contains information for only 26 countries Data are not always official statistics. Sometimes data are from a sample of schools, which might not be nationally representative |

| Data from specific destination countries |

Includes other characteristics such as age, sex, city of origin |

Difficult to obtain |

| Surveys of potential or current international students |

Rich information provided by survey questionnaires |

Lack sampling frame, therefore samples are typically not representative |

Further reading

| OECD | |

|---|---|

| 2023 | International Migration Outlook. OECD, Paris. |

| UNESCO | |

| 2015 | Facts and Figures, Mobility in higher education. |

| Kritz, M. | |

| 2006 | Globalisation and Internationalisation of Tertiary Education. Population Division, United Nations Secretariat. |

| Beine, M., R. Noël, and L. Ragot | |

| 2014 | Determinants of the International Mobility of Students. Economics of Education Review 41:40–54. |

| Han, X., G. Stocking, M. Gebbie, and R. Appelbaum | |

| 2015 | Will They Stay or Will They Go? International Graduate Students and Their Decisions to Stay or Leave the U.S. upon Graduation. PLOS ONE 10(3):e0118183. |

| Macready, C. and C. Tucker | |

| 2011 | Who Goes Where and Why?: An Overview and Analysis of Global Educational Mobility. New York: Institute of International Education. |

| Mazzarol, T. and G. Soutar | |

| 2002 | ‘Push‐pull’ Factors Influencing International Student Destination Choice. International Journal of Educational Management 16(2):82–90. |

| Tremblay, K. | |

| 2005 | Academic Mobility and Immigration. Journal of Studies in International Education 9(3):196–228. |

| Van Mol, C. & Ekamper, P. | |

| 2016 | Destination cities of European exchange students. Geografisk Tidsskrift - Danish Journal of Geography 116 (1): 85-91. |